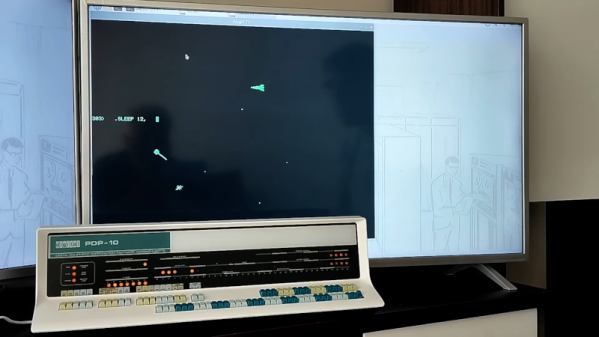

[Oscar] at Obsolescence Guaranteed is well-known for fun replicas of the PDP-8 and PDP-11 using the Raspberry Pi (along with some other simulated vintage computers). His latest attempt is the PDP-10, and you can see how it looks in the demo video below.

Watching the video will remind you of every old movie or TV show you’ve ever seen with a computer, complete with typing noise. The PDP-10, also known as a DECsystem-10, was a mainframe computer that usually ran TOPS-10. These were technically “mainframes” in 1966, although the VAX eclipsed the system. By 1983 (the end of the PDP-10’s run), around 1,500 had been sold, including ones that ran at Harvard, Stanford, Carnegie Mellon, and — of course — MIT. They also found homes at CompuServe and Tymshare.

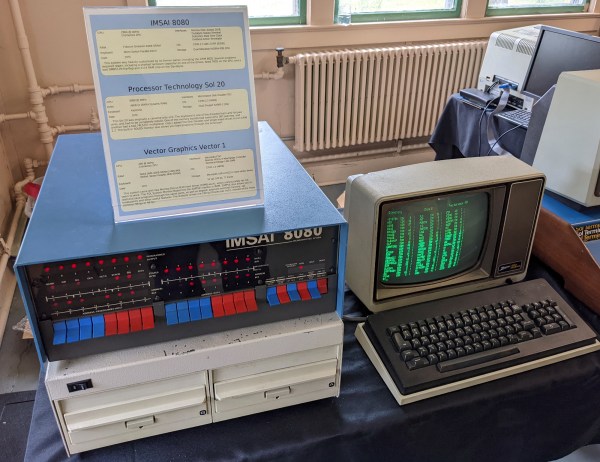

The original 36-bit machine used transistors and was relatively slow. By the 1970s, newer variants used ICs or ECL and gained some speed. A cheap version using the AM2901 bit-slice CPU and a familiar 8080 controlling the system showed up in 1978 and billed itself as “the world’s lowest cost mainframe.”

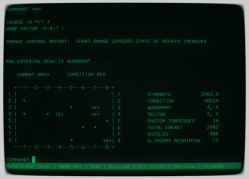

The Knight terminals were very unusual for the day. They each used a PDP-11 and had impressive graphics capability compared to similar devices from the early 1970s. You can see some of that in the demo video.

Naturally, anyone who used a PDP-10 would think a Raspberry Pi was a supercomputer, and they wouldn’t be wrong. Still, these machines were the launching pad for Adventure, Zork, and Altair Basic, which spawned Microsoft.

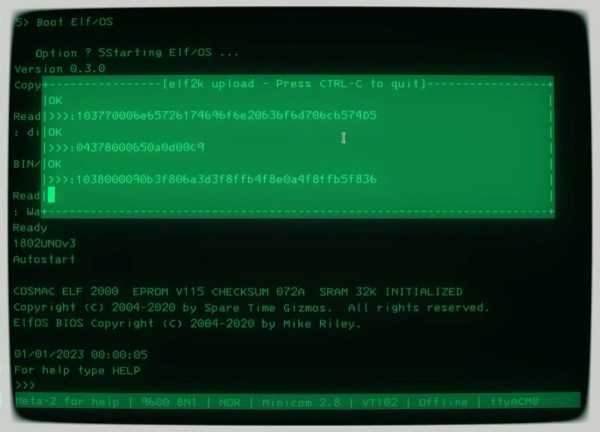

The cheap version of these used bitslice which we’ve been talking about lately. [Oscar] is also known for the KIMUno, which we converted into a COSMAC Elf.