Among the daily churn of ‘Web 3.0’, blockchains and cryptocurrency messaging, there is generally very little that feels genuinely interesting or unique enough to pay attention to. The same was true for OpenAI CEO Sam Altman’s Ethereum blockchain-based Worldcoin when it was launched in 2021 while promising many of the same things as Bitcoin and others have for years. However, with the recent introduction of the World ID protocol by Tools for Humanity (TfH) – the company founded for Worldcoin by Mr. Altman – suddenly the interest of the general public was piqued.

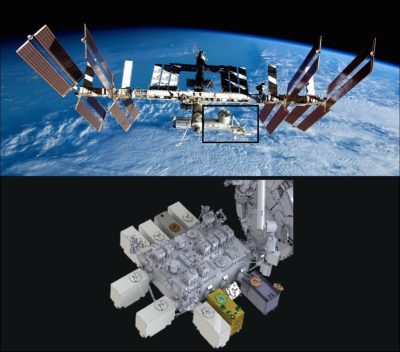

Defined by TfH as a ‘privacy-first decentralized identity protocol’ World ID is supposed to be the end-all, be-all of authentication protocols. Part of it is an ominous-looking orb contraption that performs iris scans to enroll new participants. Not only do participants get ‘free’ Worldcoins if they sign up for a World ID enrollment this way, TfH also promises that this authentication protocol can uniquely identify any person without requiring them to submit any personal data, only requiring a scan of your irises.

Essentially, this would make World ID a unique ID for every person alive today and in the future, providing much more security while preventing identity theft. This naturally raises many questions about the feasibility of using iris recognition, as well as the potential for abuse and the impact of ocular surgery and diseases. Basically, can you reduce proof of personhood to an individual’s eyes, and should you?

Continue reading “The World ID Orb And The Question Of What Defines A Person”