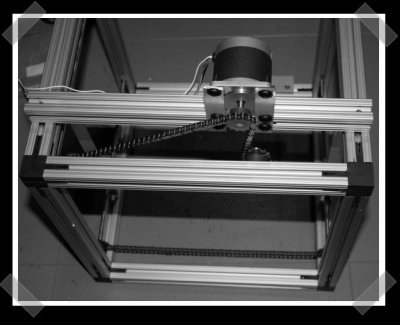

[Lou]’s been working on his own 3d printer: fabr. We find it appealing because the entry cost is quit a bit lower than something like the reprap. 80/20 isn’t that cheap, but you don’t need a large commercial laser cutter to build the chassis. The steppers he used appear to be inexpensive ones that can be salvaged from dot matrix printer. To drive it, he’s working on a custom microstepping board and hopes to eventually develop an Arduino shield to control the stepper drivers. That’s right, it’ll get an Arudino to act as the CNC control interface.

Ask Hackaday, What’s Next?

Writing for Hackaday involves drinking from the firehose of tech news, and seeing the latest and greatest of new projects and happenings in the world of hardware. But sometimes you sit back in a reflective mood, and ask yourself: didn’t this all used to be more exciting? If you too have done that, perhaps it’s worth considering how our world of hardware hacking is fueled, and what makes stuff new and interesting.

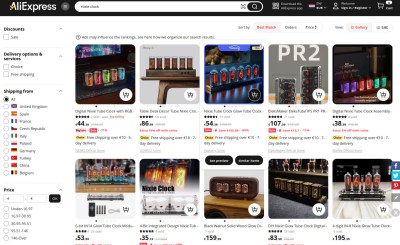

Hardware projects are like startup fads

Hardware projects are like startup fads, they follow the hype cycle. Take Nixie clocks for instance, they’re cool as heck, but here in 2024 there’s not so much that’s exciting about them. If you made one in 2010 you were the talk of the town, in 2015 everyone wanted one, but perhaps by 2020 yours was simply Yet Another Nixie Clock. Now you can buy any number of Nixie clock kits on Ali, and their shine has definitely worn off. Do you ever have the feeling that the supply of genuinely new stuff is drying up, and it’s all getting a bit samey? Perhaps it’s time to explore this topic.

I have a theory that hardware hacking goes in epochs, each one driven by a new technology. If you think about it, the Arduino was an epoch-defining moment in a readily available and easy to use microcontroller board; they may be merely a part and hugely superseded here in 2024 but back in 2008 they were nothing short of a revolution if you’d previously has a BASIC Stamp. The projects which an Arduino enabled produced a huge burst of creativity from drones to 3D printers to toaster oven reflow and many, many, more, and it’s fair to say that Hackaday owes its early-day success in no small part to that little board from Italy. To think of more examples, the advent of affordable 3D printers around the same period as the Arduino, the Raspberry Pi, and the arrival of affordable PCB manufacture from China were all similar such enabling moments. A favourite of mine are the Espressif Wi-Fi enabled microcontrollers, which produced an explosion of cheap Internet-connected projects. Suddenly having Wi-Fi went from a big deal to built-in, and an immense breadth of new projects came from those parts. Continue reading “Ask Hackaday, What’s Next?”

Hackaday Podcast Episode 262: Wheelchair Hacking, Big Little Science At Home, Arya Talks PCBs

Join Hackaday Editors Elliot Williams and Tom Nardi as they go over their favorite hacks and stories from the past week. This episode starts off with an update on Hackaday Europe 2024, which is now less than a month away, and from there dives into wheelchairs with subscription plans, using classic woodworking techniques to improve your 3D printer’s slicer, and a compendium of building systems. You’ll hear about tools for finding patterns in hex dumps, a lusciously documented gadget for sniffing utility meters, a rare connector that works with both HDMI and DisplayPort, and a low-stress shortwave radio kit with an eye-watering price tag. Finally, they’ll take a close look at a pair of articles that promise to up your KiCAD game.

Check out the links below if you want to follow along, and as always, tell us what you think about this episode in the comments!

Hackaday Prize 2023: Ending 10 Years On A High Note

It’s a fact of life — all good things must eventually come to an end. The trick is not to focus so much on the chapter that’s closing, but look ahead to what comes next. This is precisely how the Hackaday Prize ended its incredible ten-year run on Saturday during Supercon.

This final year of the competition saw some of the most impressive entries we’ve ever had, leaving us with five exceptionally promising winners. These projects exemplify the qualities that the Hackaday Prize was designed to seek out and amplify and make a perfect capstone for this grand experiment in philanthropic hacking.

Continue reading “Hackaday Prize 2023: Ending 10 Years On A High Note”

Speak To The Machine

If you own a 3D printer, CNC router, or basically anything else that makes coordinated movements with a bunch of stepper motors, chances are good that it speaks G-code. Do you?

If you were a CNC machinist back in the 1980’s, chances are very good that you’d be fluent in the language, and maybe even a couple different machines’ specialized dialects. But higher level abstractions pretty quickly took over the CAM landscape, and knowing how to navigate GUIs and do CAD became more relevant than knowing how to move the machine around by typing.

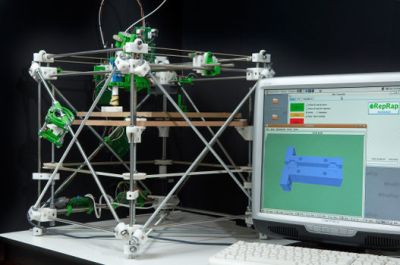

Strangely enough, I learned G-code in 2010, as the RepRap Darwin that my hackerspace needed some human wranglers. If you want to print out a 3D design today, you have a wealth of convenient slicers that’ll turn abstract geometry into G-code, but back in the day, all we had was a mess of Python scripts. Given the state of things, it was worth learning a little G-code, because even if you just wanted to print something out, it was far from plug-and-play.

For instance, it was far easier to just edit the M104 value than to change the temperature and re-slice the whole thing, which could take an appreciable amount of time back then. Honestly, we were all working on the printers as much as we were printing. Knowing how to whip up some quick bed-levelling test scripts and/or demo objects in G-code was just plain handy. And of course the people writing or tweaking the slicers had to know how to talk directly to the machine.

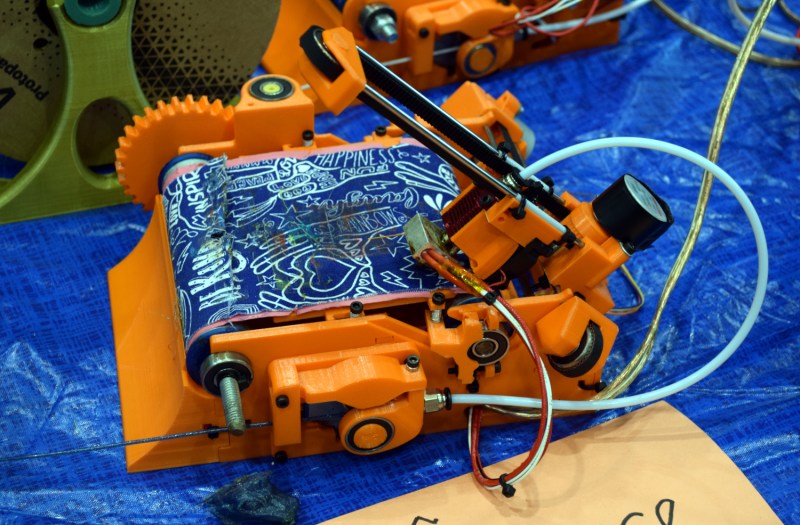

Even today, I think it’s useful to be able to speak to the machine in its native language. Case in point: the el-quicko pen-plotter I whipped together two weekends ago was actually to play around with Logo, the turtle language, with my son. It didn’t take me more than an hour or so to whip up a trivial Logo-alike (in Python) for the CNC: pen-up, pen-down, forward, turn, repeat, and subroutine definitions. Translating this all to machine moves was actually super simple, and we had a great time live-drawing with the machine.

So if you want to code for your machine, you’ll need to speak its language. A slicer is great for the one thing it does – turning an STL into G-code, but if you want to do anything a little more bespoke, you should learn G-code. And if you’ve got a 3D printer kicking around, certainly if it runs Marlin or similar firmware, you’ve got the ideal platform for exploration.

Does anyone else still play with G-code?

Brainstorming

One of the best things about hanging out with other hackers is the freewheeling brainstorming sessions that tend to occur. Case in point: I was at the Electronica trade fair and ended up hanging out with [Stephen Hawes] and [Lucian Chapar], two of the folks behind the LumenPnP open-source pick and place machine that we’ve covered a fair number of times in the past.

Among many cool features, it has a camera mounted on the parts-moving head to find the fiducial markings on the PCB. But of course, this mean a camera mounted to an almost general purpose two-axis gantry, and that sent the geeks’ minds spinning. [Stephen] was talking about how easy it would be to turn into a photo-stitching macrophotography rig, which could yield amazingly high resolution photos.

Meanwhile [Lucian] and I were thinking about how similar this gantry was to a 3D printer, and [Lucian] asked why 3D printers don’t come with cameras mounted on the hot ends. He’d even shopped this idea around at the East Coast Reprap Festival and gotten some people excited about it.

So here’s the idea: computer vision near extruder gives you real-time process control. You could use it to home the nozzle in Z. You could use it to tell when the filament has run out, or the steppers have skipped steps. If you had it really refined, you could use it to compensate other printing defects. In short, it would be a simple hardware addition that would open up a universe of computer-vision software improvements, and best of all, it’s easy enough for the home gamer to do – you’d probably only need a 3D printer.

Now I’ve shared the brainstorm with you. Hope it inspires some DIY 3DP innovation, or at least encourages you to brainstorm along below.

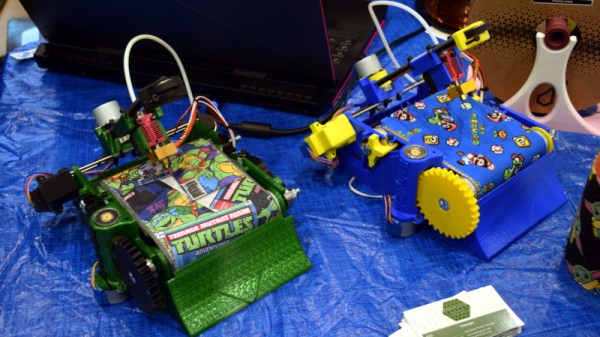

ERRF 22: Baby Belt Promises Infinite Z For Under $200

Hackaday has been reporting on belt printers for around a decade now, since MakerBot released (and then quickly pulled) an automated build platform for their very first Cupcake printer. Turns out that not only has the concept been difficult to pull off from a technical perspective, but a murky patent situation made it tricky for anyone who wanted to bring their own versions to market. For a long time they seemed like the fusion reactors of desktop 3D printing — a technology that remains perennially just outside of our grasp.

But finally, things have changed. The software has matured, and there are now several commercial belt printers on the market. The trick now, as it once was for traditional desktop 3D printing, is to bring the costs down. Enter the Baby Belt, created by [Rob Mink]. This open-source belt printer relies on light-duty components and a largely 3D printed structure to get the price point down, though some will find its diminutive dimensions a bit too limiting…even if one of its axes is technically infinite.

If you’ve already got a printer and filament to burn, [Rob] is selling the part kit for just $130 USD. But even if you opt for the full ready-to-build kit, it will only set you back $180. Considering even the cheapest belt printers on the market now have a sticker price of more than $500, that’s an impressive accomplishment.

Of course, it’s hard to compare the Baby Belt with anything else on the market. For one thing, save for a few metal rods, its frame is made almost entirely from 3D-printed parts. Rather than the NEMA 17 stepper motors that are standard on even the cheapest of traditional desktop 3D printers, this little fellow is running on the dinky 28BYJ-48 steppers that you’d expect to find in a cheap toy. Then again, considering the printer only offers 85 x 86 mm in the X and Y axis, the structure and motors don’t exactly need to be top of the line.

Of course, it’s hard to compare the Baby Belt with anything else on the market. For one thing, save for a few metal rods, its frame is made almost entirely from 3D-printed parts. Rather than the NEMA 17 stepper motors that are standard on even the cheapest of traditional desktop 3D printers, this little fellow is running on the dinky 28BYJ-48 steppers that you’d expect to find in a cheap toy. Then again, considering the printer only offers 85 x 86 mm in the X and Y axis, the structure and motors don’t exactly need to be top of the line.

What really sets this machine apart is the belt — while we’ve seen other makers go all out with their belt material, [Rob] has come up with an impressively low-tech solution. It’s a simple stack-up of construction paper, carpet tape, and fabric that you could probably put together with what you’ve got laying around the house right now.

Between that outer cloth layer and the printed frame, the Baby Belt offers a lot of room for customization, something which was on clear display at the 2022 East Coast RepRap Festival. The machines dotted several tables on the show floor, and you could tell their builders had a lot of fun making each one their own

Continue reading “ERRF 22: Baby Belt Promises Infinite Z For Under $200”