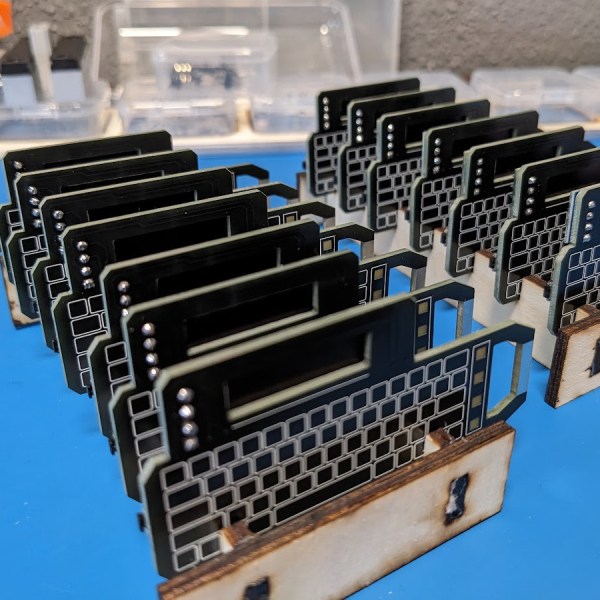

Have you built yourself a macro pad yet? They’re all sorts of programmable fun, whether you game, stream, or just plain work, and there are tons of ideas out there.

This baby runs on an ATmega32U4, which known for its Human Interface Device (HID) capabilities. [CiferTech] went with my own personal favorite, blue switches, but of course, the choice is yours.

There are not one but two linear potentiometers for volume, and these are integrated with WS2812 LEDs to show where you are, loudness-wise. For everything else, there’s an SSD1306 OLED display.

But that’s not all — there’s a secondary microcontroller, an ESP8266-07 module that in the current build serves as a packet monitor. There’s also a rotary encoder for navigating menus and such. Make it yours, and show us!

Continue reading “Keebin’ With Kristina: The One With The Folding Typewriter”