One of the entries in the Hackaday Prize Best Product competition is [x-labz]’s pocket thermal imager. It’s more than a prototype, it’s a design conceived to get out into the world and be used by many. Best Product entries are open until July 24th, and with a $30,000 cash prize on the line let’s take a look at some of the things that elevate a project to product status.

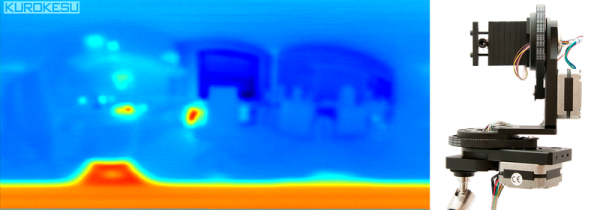

Thanks to recent advances in the state of thermal image sensors, a tool that gives you Predator vision is almost a necessity on the modern workbench. The pocket thermal imager will find drafts in your house during winter, will tell you how to cook a steak, figure out what part is shorting out in your latest electronics project, and will tell you how terrible the heated bed is on your 3D printer.

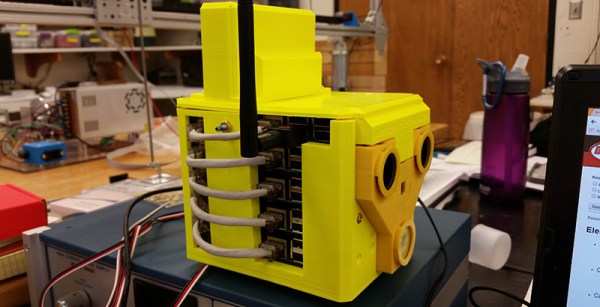

Thanks to recent advances in the state of thermal image sensors, a tool that gives you Predator vision is almost a necessity on the modern workbench. The pocket thermal imager will find drafts in your house during winter, will tell you how to cook a steak, figure out what part is shorting out in your latest electronics project, and will tell you how terrible the heated bed is on your 3D printer.

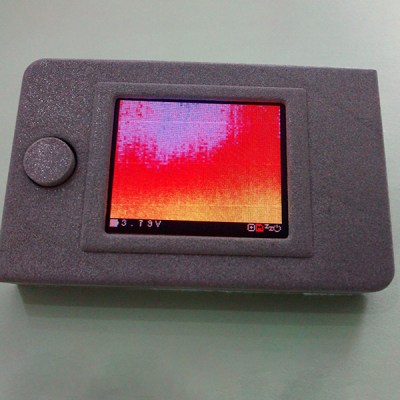

[x-labz]’s thermal camera is based around the FLIR Lepton image sensor, an 80×60 pixel thermal imaging sensor that’s good enough for most uses. This camera is soldered onto a PCB sandwich containing an Atmel SAMD21 microcontroller, full-color OLED display, SD card, and a battery management system.

What we’ve mentioned so far isn’t out of the ordinary for any other entry in the Hackaday Prize. Building something for the Best Product competition is different, though: a lot of thought has to go into the manufacturability and the fit and finish of this device. So far, everything’s looking great for [x-labz]’s camera. There’s a 3D printed case that looks like it could be easily translated into an injection-moldable shell and at least some of the parts of the user interface are unbelievably satisfying. We’re looking forward to seeing the full Bill of Materials and a business plan (a new requirement this year). That’s an area where many hardware designers lack experience; being able to study the examples from Best Product entries will be a welcomed resource.

There’s a world of difference between building a project and building a product, and the entire goal of the Best Product portion of the Hackaday Prize is to reward those people who go the extra mile as aspiring entrepreneurs and show us how that’s done. $50k in cash prizes are set aside for Best Product; $30,000 for the winner as we mentioned before, but there is also $1000 for each of the twenty entries that make it to the finals in this category in addition to some much deserved notoriety from Hackaday’s community of hardware aficionados and early adopters.