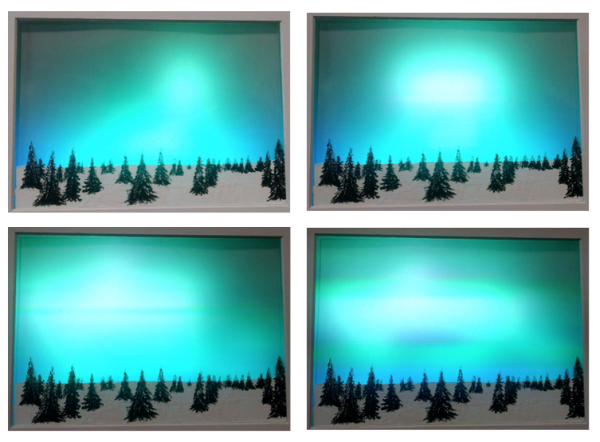

[Stef Cohen] decided to combine three different artistic mediums for her latest project. Those are painting, electronics, and software. The end goal was to recreate the aurora borealis, also known as the northern lights, in a painting.

The first step was to make the painting. [Stef] began with a shadow box. A shadow box is sort of like a picture frame that is extra deep. A snowy scene was painted directly onto the front side of the glass plate of the shadow box using acrylic paint. [Stef] painted the white, snowy ground along with some pine trees. The sky was left unpainted, in order to allow light to shine through from inside of the shadow box. A sheet of vellum paper was fixed to the inside of the glass pane. This serves to diffuse the light from the LEDs that would eventually be placed inside the box.

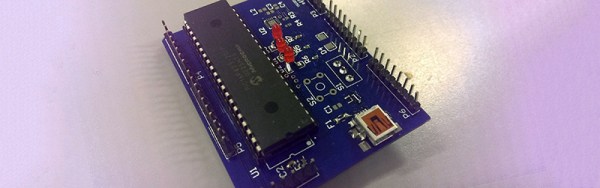

Next it was time to install the electronics. [Stef] used an off-the-shelf RGB LED matrix from Adafruit. The matrix is configured with 16 rows of 32 LEDs each. This was controlled with an Arduino Uno. The LED matrix was mounted inside the shadow box, behind the vellum paper. The Arduino code was easily written using Adafruit’s RGB Matrix Panel library.

To get the aurora effect just right, [Stef] used a clever trick. She took real world photographs of the aurora and pixelated them using Photoshop. She could then sample the color of each pixel to ensure that each LED was the appropriate color. Various functions from the Adafruit library were used to digitally paint the aurora into the LED matrix. Some subtle animations were also included to give it an extra kick.

If you’re in town Sunday morning, come nurse your hangover with [Brian], [Eric], and me. We’re headed to Va Bene Caffè at 10:30am on 8/9/15. It’s just across the street in the Cosmopolitan.

If you’re in town Sunday morning, come nurse your hangover with [Brian], [Eric], and me. We’re headed to Va Bene Caffè at 10:30am on 8/9/15. It’s just across the street in the Cosmopolitan.