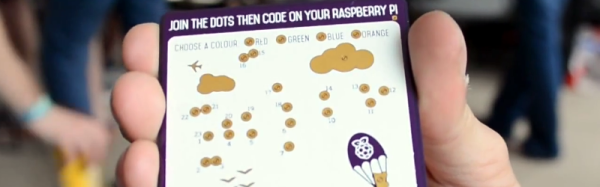

Two tables down from us at SXSW Create the Raspberry Pi foundation had a steady stream of kids playing Minecraft on Raspberry Pi, and picking up paint brushes. The painting activity was driven by a board they spun for the event that used conductive paint to control the Raspberry Pi 2.

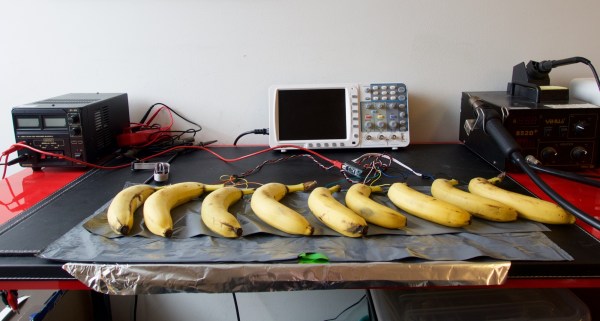

The board uses the HAT form factor which it a fancy name for a shield (also a clever one as it stands for “Hardware Attached on Top”). You can see the back side of the board in this image. It utilizes an extremely low-profile surface mount pin socket.

The board uses the HAT form factor which it a fancy name for a shield (also a clever one as it stands for “Hardware Attached on Top”). You can see the back side of the board in this image. It utilizes an extremely low-profile surface mount pin socket.

The front side exposes several circular pads of copper which build up a “connect-the-dots” game that is played by painting conductive ink on the surface. This results in an airplane being pained on the board, as well as displayed on the computer. There is a set of pads that allow the user to select what color is painted on the monitor.

We like this as a different approach to education. Kids are more than used to tapping on a touchscreen, clicking a mouse, or pounding a keyboard. But conductive ink provides several learning opportunities; the paint simply connects the inner circle with the outer circle; one of these circles is the same on every single dot (ground); anything that connects these two parts of the dot together will result in input for the computer. Great stuff!

The foundation is taking the boards to Maker Faire Bay Area next month so stop by to see these in action. You can read about the production process for the DOTS board on the Raspberry Pi website. They’re giving away a few boards to software developers who want contribute to the project. And our video interview with [Matt Richardson] is found after the break.

Continue reading “DOTS Uses Paint To Control Raspberry Pi 2”