Unimpressed by DIY wearables powered by dinky microcontrollers, [Teemu Laurila] has been working on a 3D printed head-mounted computer that puts a full-fledged Linux desktop in your field of view. It might not be as slim and ergonomic as Google Glass, but it more than makes up for it in terms of raw potential.

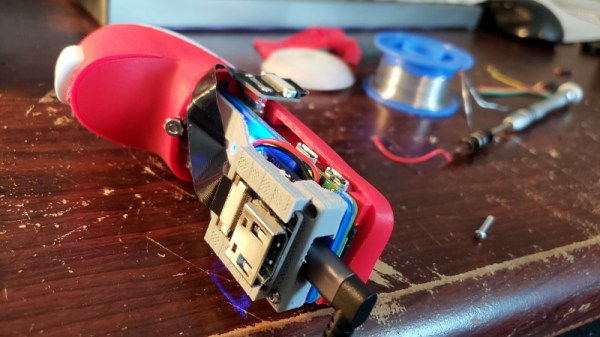

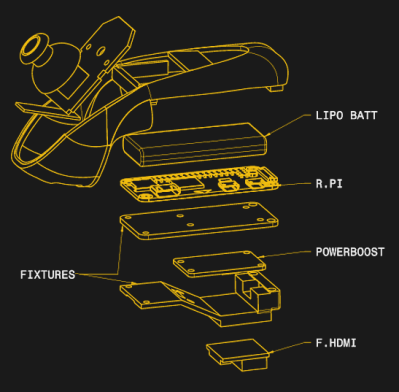

Featuring an overclocked Raspberry Pi Zero W, a ST7789VW 240×240 IPS display running at 60 Hz, and a front-mounted camera, the wearable makes a great low-cost platform for augmented reality experiments. [Teemu] has already put together an impressive hand tracking demonstration that can pick out the position of all ten fingers in near real-time. The processing has to be done on his desktop computer as the Zero isn’t quite up to the task, but as you can see in the video below, the whole thing works pretty well.

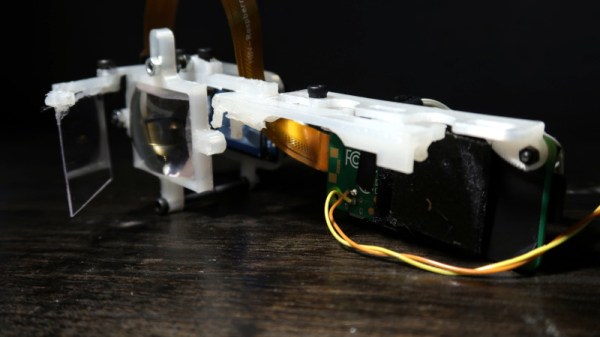

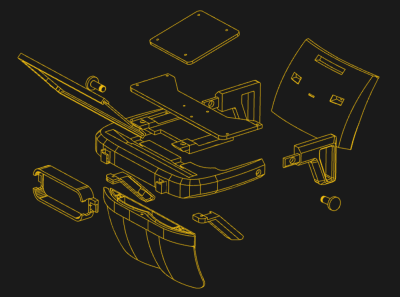

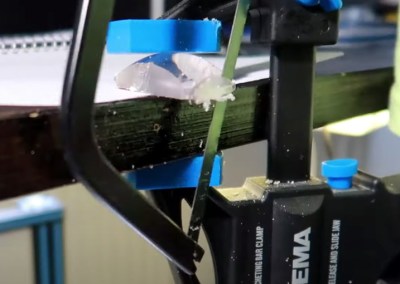

Structurally, the head-mounted unit is made up of nine 3D printed parts that clip onto a standard pair of glasses. [Teemu] says the parts will probably need to be tweaked to fit your specific frames, but the design is modular enough that it shouldn’t take too much effort. He’s using 0.6 mm PETG plastic for the front reflector, and the main lens was pulled from a cheap pair of VR goggles and manually cut down into a rectangle.

The evolution of the build has been documented in several videos, and it’s interesting to see how far the hardware has progressed in a relatively short time. The original version made [Teemu] look like he was cosplaying as a Borg drone from Star Trek, but the latest build appears to be far more practical. We still wouldn’t try to wear it on an airplane, but it would hardly look out of place at a hacker con.

Continue reading “3D Printed Smart Glasses Put Linux In Your Face”