Almost a year ago, [Jake Evill] broke his hand stopping a fight between his friend and another person. And over the next few weeks he realized how archaic plaster casts really are — clunky, smelly, itchy — not exactly conducive to healing, other than by keeping your arm completely immobilized. That’s when he came up with the Cortex Cast — a 3D printed exoskeleton cast that provides support, allows your arm to breath, and can even get wet!

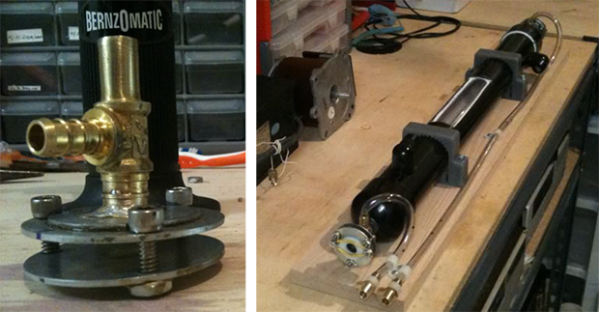

Fast forward to today, and another designer is playing with 3D printed casts — but ones that could potentially speed up the healing time! Turkish designer [Deniz Karasahin] heard about a system called the Exogen, which is a low-intensity ultrasound system which can help speed up bone repair, sometimes up to 38% faster. The problem? It doesn’t really work well with regular casts, because the transducer needs to touch the skin — the solution? A 3D printed cast of course!

You see, the ultrasound tech has been around for over 20 years, but has never really seen mainstream use because the difficulties in actually using it, until perhaps now.

Better yet, they’re also hoping to launch trials in the US soon — 3D printers are only good for trinkets and doodads? Pfft.

[Thanks William!]