Here’s a skill we should all probably have for after the apocalypse—the ability to build a cheap peristaltic pump that can transport highly viscous fluids, chunky fluids, or just plain water from point A to point B with no priming necessary. That’s exactly what [Jack Ruby] has done with some fairly common items.

He started with a springform cake pan from a thrift store, the kind where the bottom drops out like that centripetal force ride at the carnival. He’s using 2″ casters from Harbor Freight mounted to a block of wood. The casters go round and squeeze fluid through the hose, which is a nice length of heat-resistant silicone from a local homebrew shop. He’s currently using a drill to run the pump, but intends to attach a motor in the future.

[Jack]’s write-up is very thorough and amusing. Stick around to see the pump in action as well as a complete tour. You can also pump colored goo if you’re out of beer materials.

Continue reading “Peristaltic Pump Moves Fluids Uphill Both Ways”

In the wake of Google’s purchase of connected devices interest Nest, the gents at [Spark]

In the wake of Google’s purchase of connected devices interest Nest, the gents at [Spark]

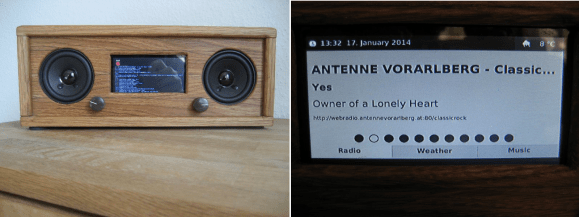

Avid Hackaday reader [Matthias] told us he takes a lot of inspiration from our site. That’s quite a compliment, because his work is both inspiring and beautiful. [Matthias] wanted to build a UI using JavaFX, so he made

Avid Hackaday reader [Matthias] told us he takes a lot of inspiration from our site. That’s quite a compliment, because his work is both inspiring and beautiful. [Matthias] wanted to build a UI using JavaFX, so he made