Need to hone up your ping pong skills? Nobody to play with? That’s okay, you could always build a hard drive powered ping pong ball launcher!

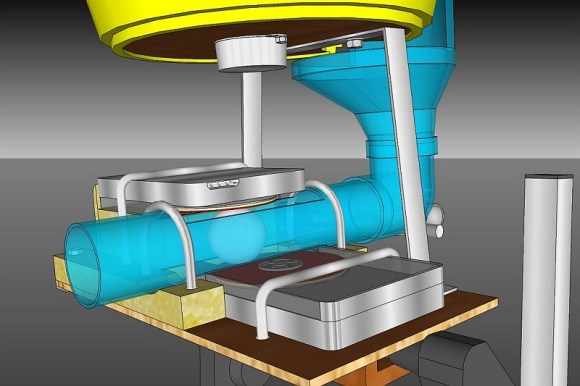

[Vendel Miskei] must like 3D modeling. He’s drawn up his entire project in some kind of 3D CAD program (the textures look vaguely like Sketchup?). It makes use of two HDDs, a computer power supply, a bunch of PVC pipe, a microwave synchronous motor, and an overhead light projector!

In order for the hard drives to grip the ping pong balls, it looks like [Vendel] removed all but one of the platters, then glued some foam to it, and what looks like the rubber from a table tennis paddle on top. He’s also made use of the original hard drive case by cutting the end off to expose half of the platter. It seems to be pretty effective!

The overhead light projector is actually just used as a convenient weighted stand for the entire project. The recycled microwave motor indexes the balls in a bucket, allowing for a huge number of balls to be queued up! Stick around after the break to see some of the awesome 3D renderings of the project, and the actual table tennis robot playing a game with its master!