OctoPrint is a great way to monitor your printer, especially with the addition of a webcam. Using a tablet or mobile phone, you can keep an eye on what the printer is doing from anywhere in the house (or world, if you take the proper precautions), saving you from having to sit with the printer as if it’s an infant. But simply watching your printer do its thing is only a small slice of the functionality offered by OctoPrint’s vast plugin community.

As [Jeremy S Cook] demonstrates, it’s fairly easy to add power control for the printer and auxiliary lighting to your OctoPrint setup. Being able to flick the lights on over the print bed is obviously a big help when monitoring it via webcam, and the ability to turn the printer off can provide some peace of mind after the print has completed. If you’re particularly brave it also means you could power on the printer and start a print completely remotely, but good luck if that first layer doesn’t go down perfectly.

As [Jeremy S Cook] demonstrates, it’s fairly easy to add power control for the printer and auxiliary lighting to your OctoPrint setup. Being able to flick the lights on over the print bed is obviously a big help when monitoring it via webcam, and the ability to turn the printer off can provide some peace of mind after the print has completed. If you’re particularly brave it also means you could power on the printer and start a print completely remotely, but good luck if that first layer doesn’t go down perfectly.

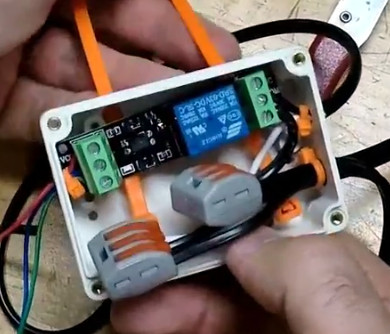

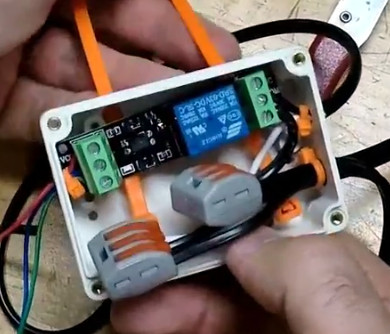

In terms of hardware, you only need some 3.3V relays for the Raspberry Pi running OctoPrint to trigger, and an enclosure to put the wiring in. [Jeremy] uses only one relay in this setup to power the printer and lights at once, but with some adjustment to the software, you could get independent control if that’s something you’re after.

On the software side [Jeremy] is using an OctoPrint plugin called “PSU Control”, which is actually intended for controlling an ATX PSU from the Pi’s GPIO pins, but the principle is close enough to throw a relay. Other plugins exist which allow for controlling a wider away of devices and GPIO pins if you want to make a fully remote controlled enclosure. Plus you can always whip up your own OctoPrint plugin if you don’t find anything that quite meets your switching needs.

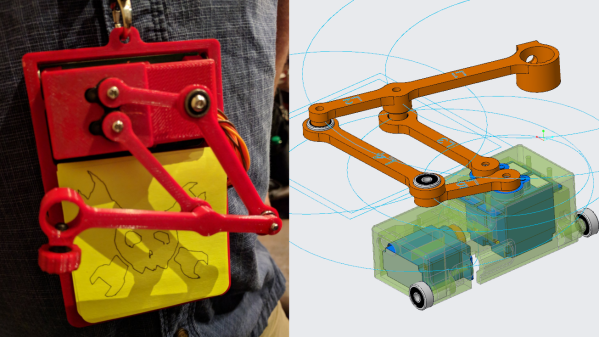

[Jeremy] previously documented his unique mount to keep his Raspberry Pi and camera pointed at his printer, which is naturally important if you want to create some cool videos with Octolapse.

Continue reading “Adding 3D Printer Power And Light Control To OctoPrint” →