Professor [Bruce Land] teaches a microcontroller class at Cornell University, and it seems like this year’s theme was selfie-taking-robots.

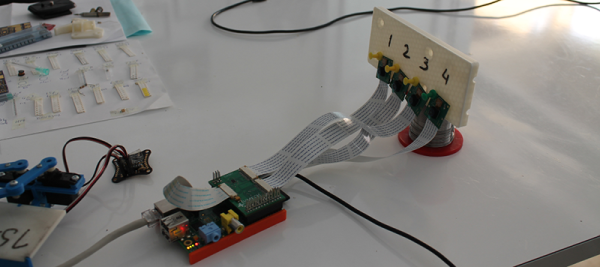

First up is a clever mix of technology by [Han, Bihan and Chuan]. What happens when you take an iPhone, three microphones and a microcontroller? The ultimate device in selfie-taking-technology, that’s what — Clap-on! The iPhone is mounted on a few servo motors which allows the bot to direct the camera towards, you guessed it, a clapping noise. On the second clap, the phone takes your picture. Cute.

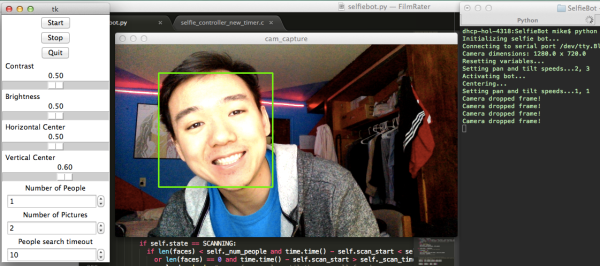

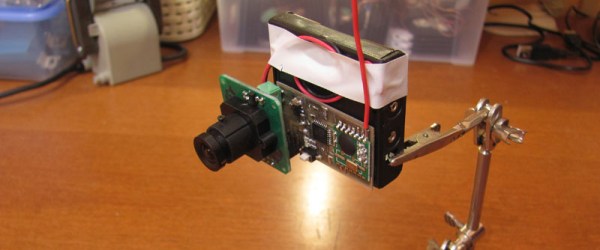

Next up is a bit more sophisticated — a facial recognition selfie-bot. This little robot can be programmed to track faces and take pictures of you and your friends when your arm is just not long enough. Not only that, you can set all kinds of parameters so you get the perfect picture. It uses OpenCV to crunch the raw data and outputs commands to an ATmega1284 which controls the servo motors that direct the camera. This project was by [Michael and Jennifer] — two fourth year students at Cornell.

Continue reading “Selfie-Bots Will Take Your Best Shots For You”