Everyone generally knows about piston and rotary engines, with many a flamewar having been waged over the pros and cons of each design. The “correct” answer is thus to combine both into a single engine design. The resulting birotary engine comes courtesy of Czech company [Knob Engines] which makes their special engine for the aviation market. The workings of this engine and why it makes perfect sense for smaller airplanes is explained by [driving 4 answers] in a recent video.

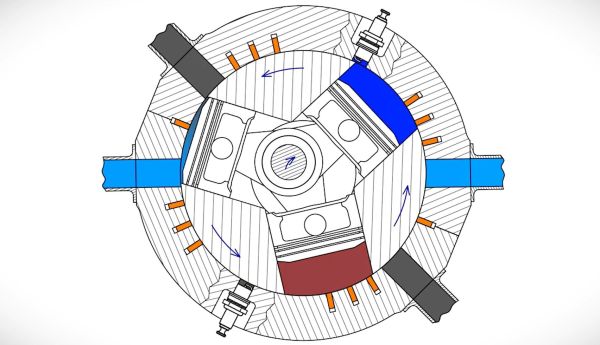

Naturally, it’s at best confusing to call an engine a “rotary”, as this covers many types of engines. One could consider the birotary engine perhaps a cross between the traditional rotary piston engines that powered early aircraft and the Wankel rotary engines that would appear much later. The fact that both the housing and the crankshaft rotate reinforces this notion of a piston rotary, while it keeps the fixed ports and glow plugs on the housing that is typical of a Wankel-style engine. Having both the housing and crankshaft rotate is also why it’s called the ‘birotary’.

The claimed benefits of this design include a small size, low vibrations, reduced gyroscopic effect due to counter-rotation, no apex seals, and less mechanically complex than a piston engine. This comes at the cost of a very short stroke length and thus the need for a relatively high RPM and slow transition between power output levels, but those disadvantages are why small airplanes and UAVs are being targeted.