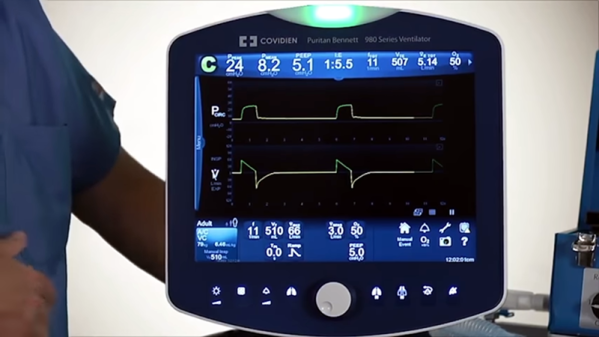

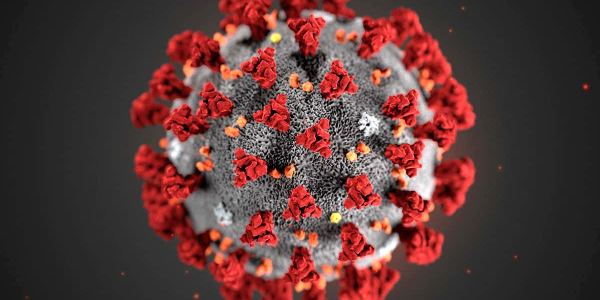

The current COVID-19 pandemic is rife with problems that hackers have attacked with gusto. From 3D printed face shields and homebrew face masks to replacements for full-fledged mechanical ventilators, the outpouring of ideas has been inspirational and heartwarming. At the same time there have been many efforts in a different area: research aimed at fighting the virus itself.

Getting to the root of the problem seems to have the most potential for ending this pandemic and getting ahead of future ones, and that’s the “know your enemy” problem that the distributed computing effort known as Folding@Home aims to address. Millions of people have signed up to donate cycles from spare PCs and GPUs, and in the process have created the largest supercomputer in history.

But what exactly are all these exaFLOPS being used for? Why is protein folding something to direct so much computational might toward? What’s the biochemistry behind this, and why do proteins need to fold in the first place? Here’s a brief look at protein folding: what it is, how it happens, and why it’s important.