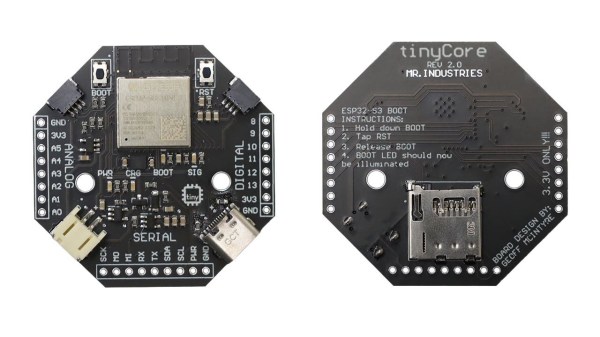

Looking for an educational microcontroller board to get you or a loved one into electronics? Consider the tinyCore – a small and nifty octagon-shaped ESP32 board by [MR. INDUSTRIES], simplified for learning yet featureful enough to offer plenty of growth, and fully open.

The tinyCore board’s octagonal shape makes it more flexible for building wearables than the vaguely rectangular boards we’re used to, and it’s got a good few onboard gadgets. Apart from already expected WiFi, BLE, and GPIOs, you get battery management, a 6DoF IMU (LSM6DSOX) in the center of the board, a micro SD card slot for all your data needs, and two QWIIC connectors. As such, you could easily turn it into, say, a smartwatch, a motion-sensitive tracker, or a controller for a small robot – there’s even a few sample projects for you to try.

You can buy one, or assemble a few yourself thanks to the open-source-ness – and, to us, the biggest factor is the [MR.INDUSTRIES] community, with documentation, examples, and people learning with this board and sharing what they make. Want a device with a big display that similarly wields a library of examples and a community? Perhaps check out the Cheap Yellow Display hacks!

Continue reading “TinyCore Board Teaches Core Microcontroller Concepts”

![[Piers] explains his code](https://hackaday.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/One-ROM-PIO-banner.jpg?w=600&h=450)