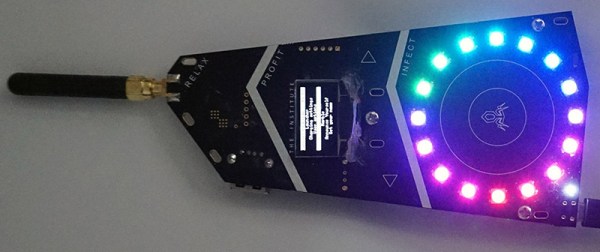

[Bunnie] was at Burning Man this year, and to illuminate his camp members in the dark and dusty nights of the playa, he created a blinky badge. This isn’t just any badge stuffed with RGB LEDs; each of the badges were unique by the end of Burning Man. These badges were made unique not by twiddling dials or pressing buttons; all the color patterns were bred with badge sex.

This social experiment to replicate nature’s most popular means of creating more nature is built around a peer to peer radio. Each badge is equipped with a radio, a circle of RGB LEDs, and a bit of code that expresses the pattern of lights on the badge as a sequence of genes. When one badge gives consent to another badge, they ‘breed’, creating a new pattern of lights. If you’re wondering about the specifics of the act, each badge is a hermaphrodite, and each badge transmits a ‘sperm’ to fertilize the other plant’s ‘egg’. There’s even a rare trait included in the genome of the badge; each badge has a 3% chance of having a white pixel that moves around the circle of LEDs. [Bunnie] found this trait was more common after a few days, suggesting that people were selectively breeding their badges.

Of course, finding potential mates is a paramount concern for any sexual organism, and the sex badge has this covered, too. The 900MHz radio listens for other badges in close proximity, and when any are found their owners are displayed on an OLED display. This came in handy for [Bunnie] more than a few times – there’s no phones out there, and simply knowing your friends are within a hundred meters or so is a big help.

The entire badge platform is documented online, along with the code and spec for badge genes. Badges with some sort of wireless communication have been around for a while, but this is the first time that communication has been used for something more than sharing contact information or implementing a chat room. It’s a great idea, and something we hope to see more of in future con badges.

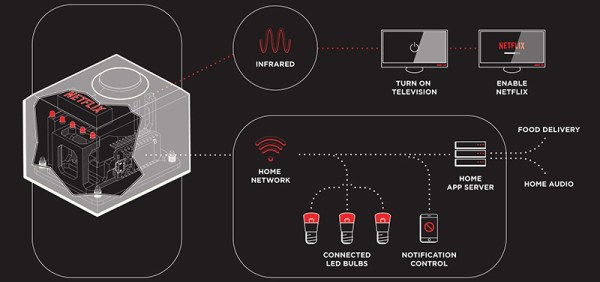

The Netflix Switch is a relatively simple device powered by a

The Netflix Switch is a relatively simple device powered by a