When [Matt] started building his multirotor helicopter, he was far too involved with building his craft than worrying about small details like how to actually control his helicopter. Everything worked out in the end, though, thanks to his homebrew RC setup built out of a USB joystick and a few XBees.

After a few initial revisions and a lot of chatting on a multirotor IRC room, [Matt] stumbled across the idea of using pulse-position modulation for his radio control setup.

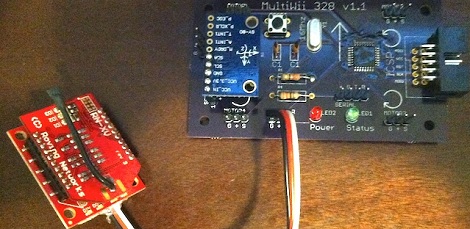

After a few more revisions, [Matt] settled on using an Arduino Pro Mini for his flight computer, paired with a WiFly module. By putting his multicopter into Ad-hoc mode, he can connect to the copter with his laptop via WiFi and send commands without the need for a second XBee.

Now, whenever [Matt] wants to fly his multicopter, he plugs the WiFly module into his MultiWii board, connects his laptop to the copter, and runs a small Python script. It may not be easier than buying a nice Futaba transmitter, but [Matt] can easily expand his setup as the capabilities of his copter fleet grows.

Video of [Matt]’s copter in flight after the break.

Continue reading “Controlling A Quadcopter With A Homebrew Remote”