It’s been a long time since vacuum tubes were cutting-edge technology, but that doesn’t mean they don’t show up around here once in a while. And when they do, we like to feature them, because there’s still something charming, nay, romantic about a circuit built around hot glass and metal. To wit, we present this compact two-tube “spy radio” transmitter.

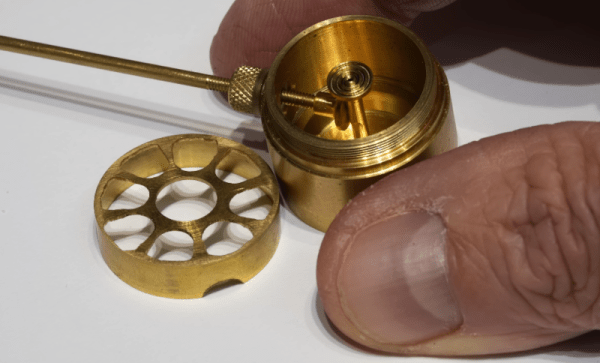

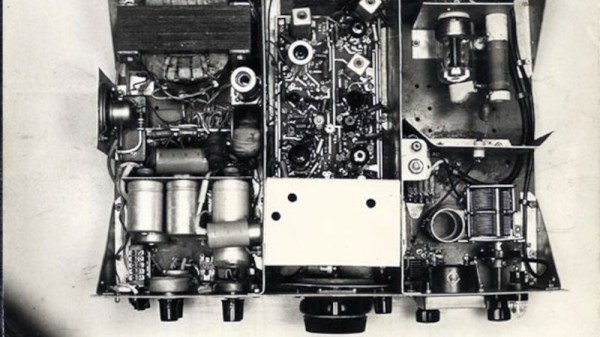

From the look around his shack — which we love, by the way — [Helge Fykse (LA6NCA)] really has a thing for old technology. The typewriter, the rotary phones, the boat-anchor receiver — they all contribute to the retro feel of the space, as well as the circuit he’s working on. The transmitter’s design is about as simple as can be: one tube serves as a crystal-controlled oscillator, while the other tube acts as a power amplifier to boost the output. The tiny transmitter is built into a small metal box, which is stuffed with the resistors, capacitors, and homebrew inductors needed to complete the circuit. Almost every component used has a vintage look; we especially love those color-coded mica caps. Aside from PCB backplane, the only real nod to modernity in the build is the use of 3D printed forms for the coils.

But does it work? Of course it does! The video below shows [Helge] making a contact on the 80-meter band over a distance of 200 or so kilometers with just over a watt of power. The whole project is an excellent demonstration of just how simple radio communications can be, as well as how continuous wave (CW) modulation really optimizes QRP setups like this.

Continue reading “Two-Tube Spy Transmitter Fits In The Palm Of Your Hand”