When do you post your projects? When they’re done? When they’re to the basic prototype stage? Or all along the way, from their very conception? All of these have their merits, and their champions.

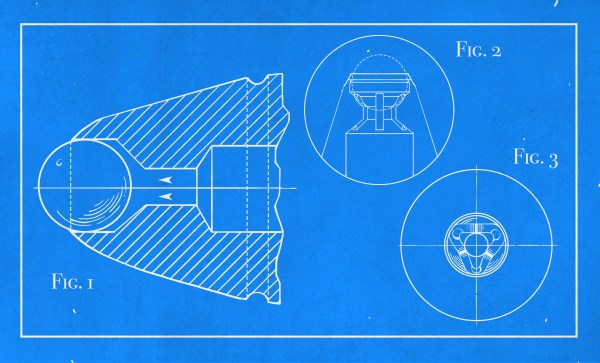

In the post-all-along-the-way corner, we have Hackaday’s own [Arya Voronova], who outlines the many ways that you can start documenting your project before it’s even a fully fledged project. She calls these tidbits “breadcrumbs”, and it strikes me as being a lot like keeping a logbook, but doing it in public. The advantages? Instead of just you, everyone on the Internet can see what you’re up to. This means they can offer help, give you parts recommendations, and find that incorrect pinout that one pair of eyes would have missed. It takes a lot of courage to post your unfinished business for all to see, but ironically, that’s the stage of the project where you stand to gain the most from the exposure.

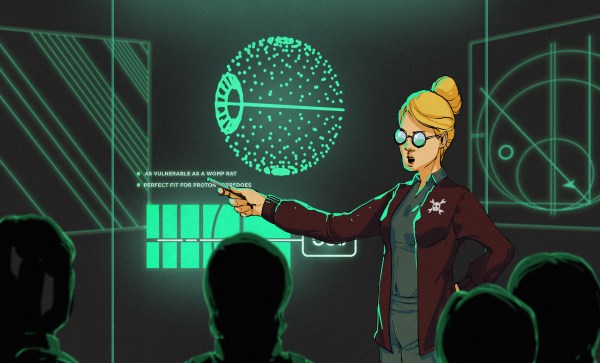

On the opposite end of the spectrum are the folks who document their projects at the very end. We see a ton of these on Hackaday.io and in people’s personal blogs. It’s a great service to the community, frankly, because at that point, you’re already done with the project. This is the point where the reward, for you, is at its minimum, but it’s also the point where you feel least inhibited about sharing if you’re one of those people who are afraid of showing your work off half-done. The risk here, if you’re like me, is that you’re already on to the next project when one is “done”, and going back over it to make notes seems superfluous. Those of you who do it regardless, we salute you!

And then there’s the middle ground. When you’re about one third of the way done, you realize that you might have something half workable, and you start taking a photo or two, or maybe even typing words into a computer. Your git logs start to contain more than just “fixed more stuff” for each check-in, because what if someone else actually reads this? Maybe you’re to the point where you’ve just made the nice box to put it in, and you’re not sure if you’ll ever go back and untangle that rat’s nest, so you take a couple of pictures of the innards before you hot glue it down.

I’m a little ashamed I’m probably on the “post only when it’s done” end of things than is healthy, mostly because I don’t have the aforementioned strength of will to go back. What about you?