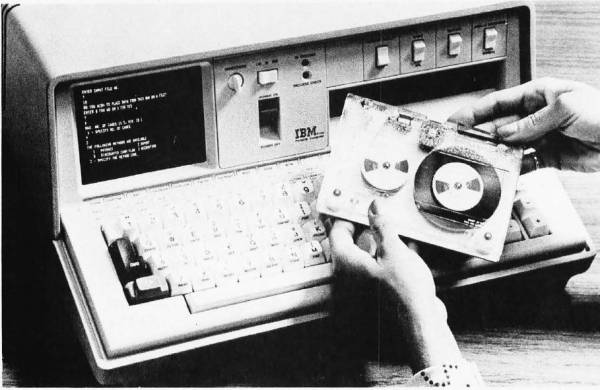

The 1970s was a somewhat awkward phase for the computer industry — as hulking, room-sized mainframes became ever smaller and the concept of home and portable computers more capable than a basic calculator began to gain traction. Amidst all of this, two interpreted programming languages saw themselves being used the most: BASIC and APL, with the latter being IBM’s programming language of choice for its mainframes. The advantages of being able to run APL on a single-user, portable system, eventually led to the IBM 5100. Its story is succinctly summarized by [Bradford Morgan White] in a recent article.

Although probably not well-known to the average computer use, APL (A Programming Language) is a multi-dimensional array-based language that uses a range of special graphic symbols that are often imprinted on the keyboard for ease of entry.

It excels at concisely describing complex functions, such as the example provided on the APL Wikipedia entry for picking 6 pseudo-random, non-repeating integers between 1 and 40 and sorting them in ascending order:

x[⍋x←6?40]

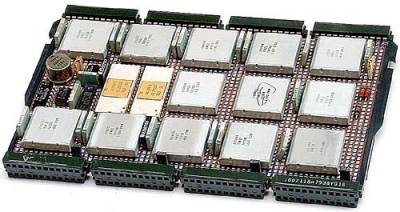

Part of what made it possible to bring the power of APL processing to a portable system like the IBM 5100 was the IBM PALM processor, which implemented an emulator in microcode to allow e.g. running System/360 APL code on a 5100, as well as BASIC.

Despite [Bradford]’s claim that the 5100 was not a commercial success, it’s important to remember the target market. With a price tag of tens of thousands of (inflation-adjusted 2023) dollars, it bridged the gap between a multi-user mainframe with APL and far less capable single-user systems that generally only managed BASIC. This is reflected in that the Commodore SuperPET supported APL, and the 5100 was followed by the 5110 and 5120 systems, and that today you can download GNU APL which implements the ISO/IEC 13751:2001 (APL2) standard.

We’ve previously looked at the Canadian-made MCM/70, another portable APL machine that embodied the cyberdeck aesthetic before William Gibson even gave it a name.

Top image: The IBM 5100, image from December 1975 issue of BYTE.

Thanks to [Stephen Walters] for the tip.