Not every talk at the Chaos Communication Congress is about hacking computers. In this outstanding and educational talk, [Michael Büker] walks us through the history of our understanding of the planets.

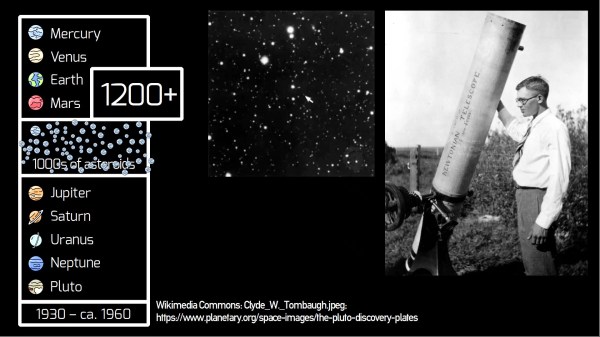

The question “What is a planet?” is probably more about the astronomers doing the looking than the celestial bodies that they’re looking for. In the earliest days, the Sun and the Moon were counted in. They got kicked out soon, but then when we started being able to see asteroids, Ceres, Vesta, and Juno made the list. But by counting all the asteroids, the number got up above 1,200, and it got all too crazy.

Viewed in this longer context, the previously modern idea of having nine planets, which came about in the 1960s and lasted only until 2006, was a blip on the screen. And if you are still a Pluto-is-a-planet holdout, like we were, [Michael]’s argument that counting all the Trans-Neptunian Objects would lead to madness is pretty convincing. It sure would make it harder to build an orrery.

His conclusion is simple and straightforward and has the ring of truth: the solar system is full of bodies, and some are large, and some are small. Some are in regular orbits, and some are not. Which we call “planets” and which we don’t is really about our perception of them and trying to fit this multiplicity into simple classification schemas. What’s in a name, anyway?