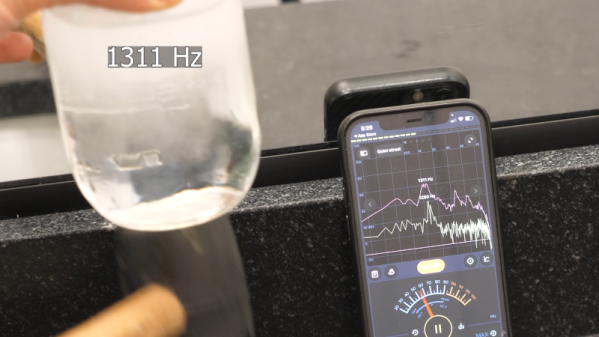

There’s an old joke about how to tell how tall a building is using a barometer. The funniest answer is to find the building owner and offer them a nice barometer in exchange for the information. We wonder if [DiodeGoneWild] has heard that one since his recent video details how to measure temperatures using an ohmmeter.

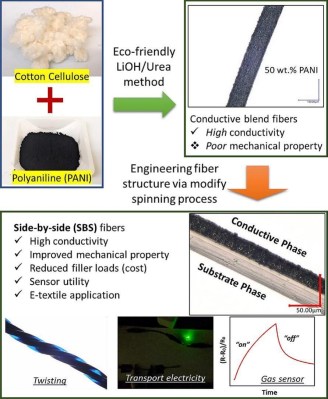

The idea is that wire changes its resistance based on temperature. So if you know the resistance of a lot of wire — maybe a coil — at room temperature and you can measure the resistance at temperature, it is entirely feasible to calculate the amount of temperature that would cause this rise in resistance.

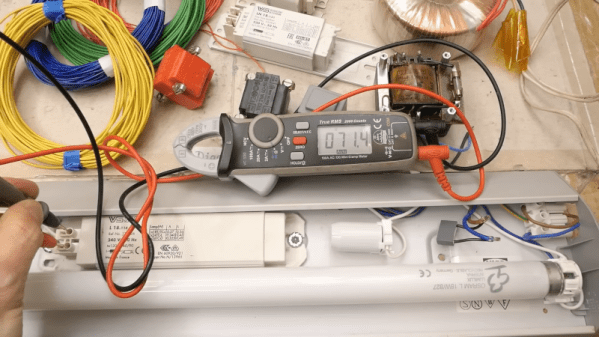

Of course, there are many ways to measure resistance, too. It’s probably possible to measure parameters like operating current and estimate temperature for at least some circuits. The wire’s material also plays a part, and the online calculator lets you choose copper, aluminum, iron, or tungsten. You also need a lot of wire, a very accurate resistance measurement, or, preferably, both.

There are many ways to accurately measure resistance, of course. Then again, you can also get resistors specifically for the job.