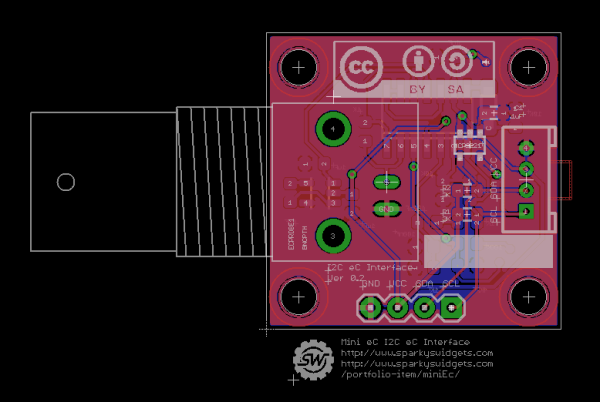

Ever pried apart an LCD? If so, you’ve likely stumbled at the unassuming zebra strip — the pliable connector that makes bridging PCB pads to glass traces look effortless. [Chuck] recently set out to test if he could hack together his own zebra strip using conductive TPU and a 3D printer.

[Chuck] started by printing alternating bands of conductive and non-conductive TPU, aiming to mimic the compressible, striped conductor. Despite careful tuning and slow prints, the results were mixed to say the least. The conductive TPU measured a whopping 16 megaohms, barely touching the definition of conductivity! LEDs stayed dark, multimeters sulked, and frustration mounted. Not one to give up, [Chuck] took to his trusty Proto-pasta conductive PLA, and got bright, blinky success. It left no room for flexibility, though.

It would appear that conductive TPU still isn’t quite ready for prime time in fine-pitch interconnects. But if you find a better filament – or fancy prototyping your own zebra strip – jump in! We’d love to hear about your attempts in the comments.

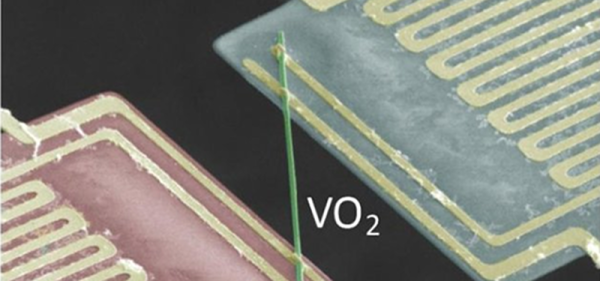

probed per run, but however it works it produces some interesting, almost random results. The premise is that the point-to-point surface resistivity is unpredictable due to the chaotically formed crystals all jumbled up, but somehow uses these measured data to generate some waveshapes vaguely reminiscent of the resistivity profile of the sample, the output of which is then fed into a sound synthesis application and pumped out of a speaker. It certainly looks fun.

probed per run, but however it works it produces some interesting, almost random results. The premise is that the point-to-point surface resistivity is unpredictable due to the chaotically formed crystals all jumbled up, but somehow uses these measured data to generate some waveshapes vaguely reminiscent of the resistivity profile of the sample, the output of which is then fed into a sound synthesis application and pumped out of a speaker. It certainly looks fun.