For fans of retro games, Pac-Man is nothing short of iconic—a game so loved it’s been ported to nearly every console imaginable. But the Atari 2600 version, released in 1982, left players scratching their heads – as laid out in a video by [Almost Something]. Atari had licensed Pac-Man to ride the wave of its arcade success, but the home version, programmed solely by [Todd Fry], missed the mark, turning an arcade icon into a surprising lesson in over-ambitious marketing.

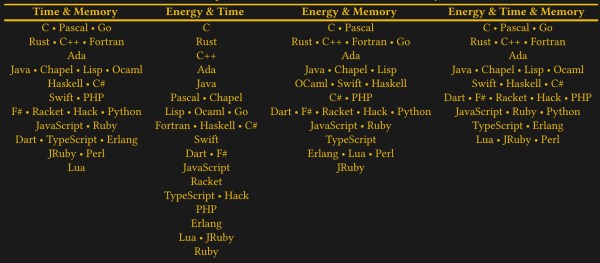

Despite the hype, [Fry] faced an almost impossible task: translating Pac-Man’s detailed graphics and complex gameplay to the Atari’s limited 4 K cartridge with only 128 bytes of RAM. Atari’s strict limitations on black backgrounds and its choice to cut costs by sticking with a 4 K cartridge left the game barely recognizable. The famous pellet-chomping maze became simpler, colors were changed, and the iconic ghosts—reduced to single colors—flickered constantly. And then, Atari went all in, producing twelve million copies, betting on the success of universal appeal. In a twist, Pac-Man did sell in record numbers (over seven million copies) but still fell short of Atari’s expectations, leaving millions of unsold cartridges eventually dumped in a New Mexico landfill.

This debacle even kind of marked Atari’s 1983 decline. Still, Pac-Man survived the hiccup, evolving and outlasting its flawed adaptation on the 2600. If you’re interested in learning more about the ins and outs of game ports, check out the fantastic talk [Bob Hickman] gave during Supercon 2023.

Continue reading “Atari’s Pac-Man Flop: How A Classic Went Off-Course”