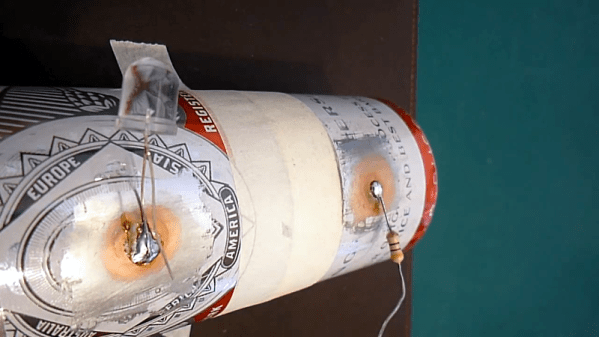

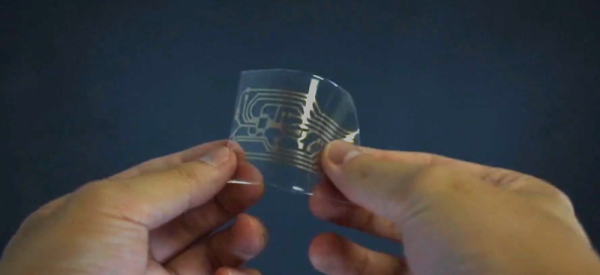

If you’ve ever tried to solder to aluminum, you know it isn’t easy without some kind of special technique. [SimpleTronic] recently showed a method that chemically plates copper onto aluminum and allows you to solder easily. We aren’t chemists, so we aren’t sure if this is the best way or not, but the chemicals include salt, copper sulfate (found in pool stores), ferric chloride as you’d use for etching PCBs, and water.

Once you have bare aluminum, you prepare a solution from the copper sulfate and just a little bit of ferric chloride. Using salt with that solution apparently removes oxidation from the aluminum. Then using the same solution without the salt puts a copper coating on the metal that you can use for soldering. You can see a video of the process below.