Plenty of projects we see here could easily be purchased in some form or other. Robot arms, home automation, drones, and even some software can all be had with a quick internet search, to be sure. But there’s no fun in simply buying something when it can be built instead. The same goes for tools as well, and this homemade drill press from [ericinventor] shows that it’s not only possible to build your own tools rather than buy them, but often it’s cheaper as well.

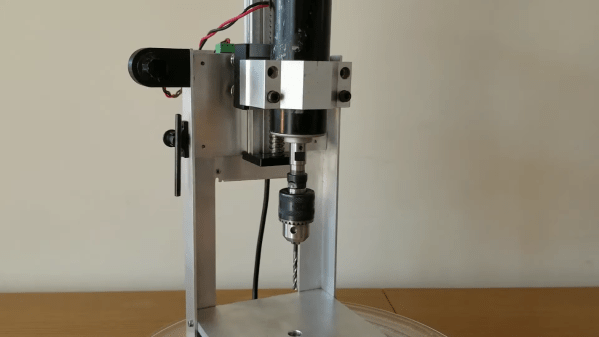

This mini drill press has every feature we could think of needing in a tool like this. It uses off-the-shelf components including the motor and linear bearing carriage (which was actually salvaged from the Z-axis of a CNC machine). The chassis was built from stock aluminum and bolted together, making sure to keep everything square so that the drill press is as precise as possible. The movement is controlled from a set of 3D printed gears which are turned by hand.

The drill press is capable of drilling holes in most materials, including metal, and although small it would be great for precision work. [ericinventor] notes that it’s not necessary to use a separate motor, and that it’s possible to use this build with a Dremel tool if one is already available to you. Either way, it’s a handy tool to have around the shop, and with only a few modifications it might be usable as a mill as well.

Continue reading “This DIY Drill Press Is Very Well Executed”