The Frame AR glasses by Brilliant Labs, which contain a small display, are an entirely different approach to hacker-accessible and affordable AR glasses. [Karl Guttag] has shared his thoughts and analysis of how the Frame glasses work and are constructed, as usual leveraging his long years of industry experience as he analyzes consumer display devices.

It’s often said that in engineering, everything is a tradeoff. This is especially apparent in products like near-eye displays, and [Karl] discusses the Frame glasses’ tradeoffs while comparing and contrasting them with the choices other designs have made. He delves into the optical architecture, explaining its impact on the user experience and the different challenges of different optical designs.

It’s often said that in engineering, everything is a tradeoff. This is especially apparent in products like near-eye displays, and [Karl] discusses the Frame glasses’ tradeoffs while comparing and contrasting them with the choices other designs have made. He delves into the optical architecture, explaining its impact on the user experience and the different challenges of different optical designs.

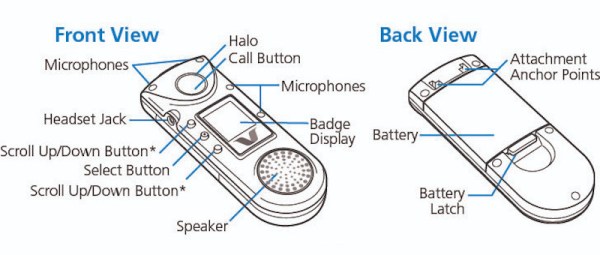

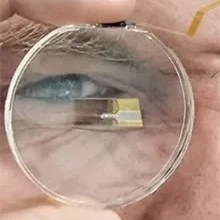

The Frame glasses are Brilliant Labs’ second product with their first being the Monocle, an unusual and inventive sort of self-contained clip-on unit. Monocle’s hacker-accessible design and documentation really impressed us, and there’s a pretty clear lineage from Monocle to Frame as products. Frame are essentially a pair of glasses that incorporate a Monocle into one of the lenses, aiming to be able to act as a set of AI-empowered prescription glasses that include a small display.

We recommend reading the entire article for a full roundup, but the short version is that it looks like many of Frame’s design choices prioritize a functional device with low cost, low weight, using non-specialized and economical hardware and parts. This brings some disadvantages, such as a visible “eye glow” from the front due to display architecture, a visible seam between optical elements, and limited display brightness due to the optical setup. That being said, they aim to be hacker-accessible and open source, and are reasonably priced at 349 USD. If Monocle intrigued you, Frame seems to have many of the same bones.