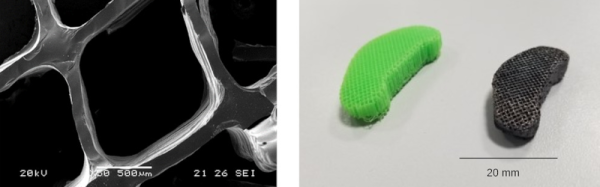

What do you get when you cross a day job as a Medical Histopathologist with an interest in 3D printing and programming? You get a fully-baked Open Source microscope, specifically the Portable Upgradeable Modular Affordable (or PUMA), that’s what. And this is no toy microscope. By combining a sprinkle of off-the-shelf electronics available from pretty much anywhere, a pound or two of filament, and a dash of high quality optical parts, PUMA cooks up quite possibly one of the best open source microscopy experiences we’ve ever tasted.

GitHub user [TadPath] works as a medical pathologist and clearly knows a thing or two about what makes a great instrument, so it is a genuine joy for us to see this tasty project laid out in such a complete fashion. Many a time we’ve looked into an high-profile project, only to find a pile of STL files and some hard to source special parts. But not here. This is deliberately designed to be buildable by practically anyone with access to a 3D printer and an eBay account.

The project is not currently certified for medical diagnostics use, but that is likely only a matter of money and time. The value for education and research (especially in developing nations) cannot really be overstated.

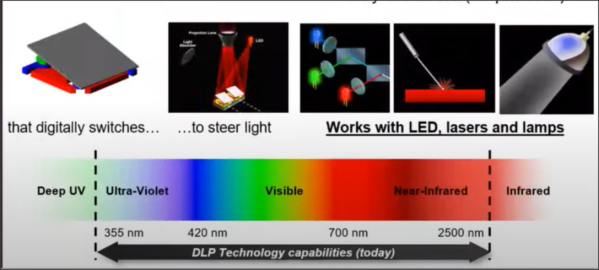

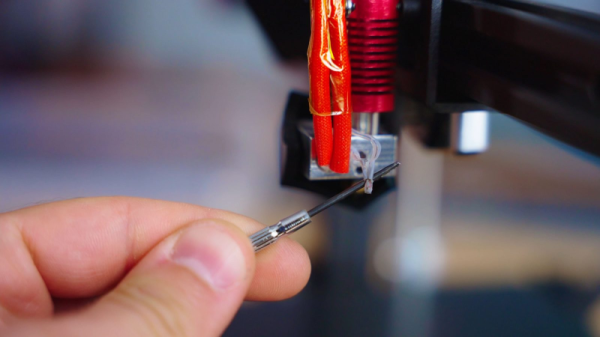

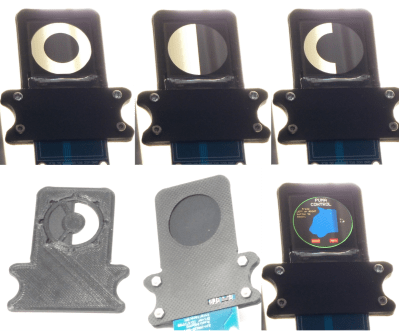

The modularity allows a wide range of configurations from simple ambient light illumination, with a single objective, great for using out in the field without electricity, right up to a trinocular setup with TFT-based spatial light modulator enabling advanced methods such as Schlieren phase contrast (which allows visualisation of fluid flow inside a live cell, for example) and a heads-up display for making measurements from the sample. Add into the mix that PUMA is specifically designed to be quickly and easily broken down in the field, that helps busy researchers on the go, out in the sticks.

The GitHub repo has all the details you could need to build your own configuration and appropriate add-ons, everything from CAD files (FreeCAD source, so you can remix it to your heart’s content) and a detailed Bill-of-Materials for sourcing parts.

We covered fluorescence microscopy before, as well as many many other microscope related stories over the years, because quite simply, microscopes are a very important topic. Heck, this humble scribe has a binocular and a trinocular microscope on the bench next to him, and doesn’t even consider that unusual. If you’re hungry for an easily hackable, extendable and cost-effective scope, then this may be just the dish you were looking for.

Continue reading “Highly Configurable Open Source Microscope Cooked Up In FreeCAD”