The history of the diode is a fun one as it’s rife with accidental discoveries, sometimes having to wait decades for a use for what was found. Two examples of that are our first two topics: thermionic emission and semiconductor diodes. So let’s dive in.

Vacuum Tubes/Thermionic Diodes

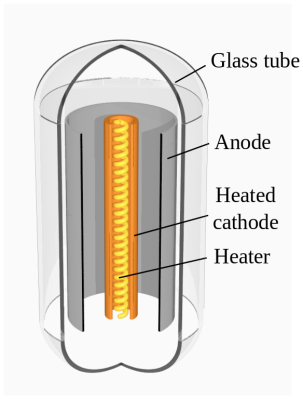

Our first accidental discovery was of thermionic emission, which many years later lead to the vacuum tube. Thermionic emission is basically heating a metal, or a coated metal, causing the emission of electrons from its surface.

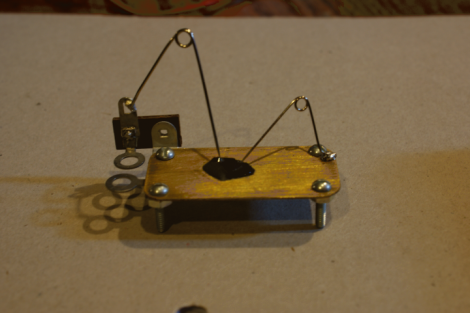

In 1873 Frederick Guthrie had charged his electroscope positively and then brought a piece of white-hot metal near the electroscope’s terminal. The white-hot metal emitted electrons to the terminal, which of course neutralized the electroscope’s positive charge, causing the leafs to come together. A negatively charged electroscope can’t be discharged this way though, since the hot metal emits electrons only, i.e. negative charge. Thus the direction of electron flow was one-way and the earliest diode was born.

Thomas Edison independently discovered this effect in 1880 when trying to work out why the carbon-filaments in his light bulbs were often burning out at their positive-connected ends. In exploring the problem, he created a special evacuated bulb wherein he had a piece of metal connected to the positive end of the circuit and held near the filament. He found that an invisible current flowed from the filament to the metal. For this reason, thermionic emission is sometimes referred to as the Edison effect.

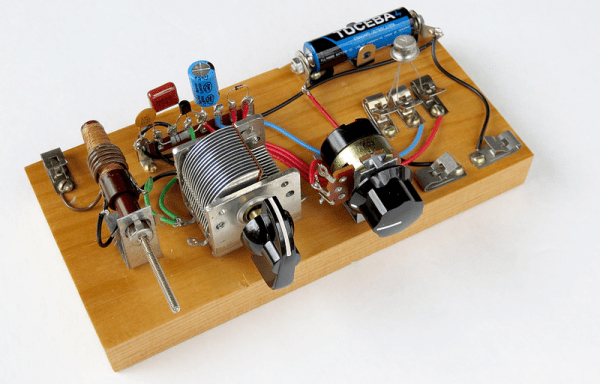

Vacuum tubes began to be replaced in power supplies in the 1940s by selenium diodes and in the 1960s by semiconductor diodes but are still used today in high power applications. There’s also been a resurgence in their use by audiophiles and recording studios. But that’s only the start of our history.