Those of us ancient enough to remember the time, or even having grown up during the heyday of the 8-bit home computer, may recall the pain of trying to make your latest creation work on another brand of computer. They all spoke some variant of BASIC, yet were wildly incompatible with each other regardless. BASICODE was a neat solution to this, acting as an early compatibility standard and abstraction layer. It was essentially a standardized BASIC subset with a few extra routines specialized per platform.

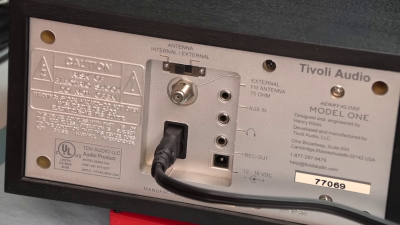

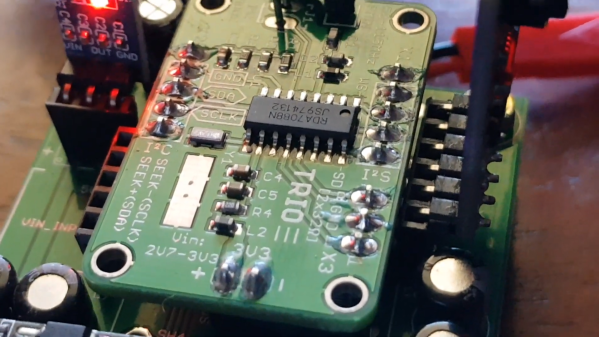

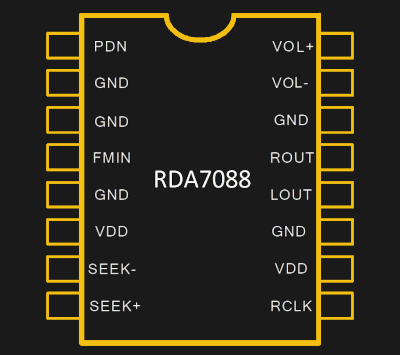

But that’s only part of the story. The BASICODE standard program was invented by Dutch radio engineer Hessel de Vries, who worked for the Dutch national radio broadcaster Nederlandse Omroep Stichting (NOS). It was designed to be broadcast over FM radio! The idea of standardization and free national deployment was brilliant and lasted until 1992, when corporate changes and technological advancements ultimately led to its decline.

Continue reading “BASICODE: A Bit Like Java, But From The 1980s”