Othermachine Co. is not a big company. Their flagship product, the Othermill, is made in small, careful batches. As we’ve seen with other small hardware companies, the manufacturing process can make or break the company. While we toured their factory in Berkeley California, a few interesting things stood out to us about their process which showed their manufacturing competence.

It’s not often that small companies share the secrets of their shop floor. Many of us have dreams of selling kits, so any lessons that can be learned from those who have come before is valuable. The goal of any manufacturing process optimization is to reduce cost while simultaneously maintaining or increasing quality. Despite what cynics would like to believe, this is often entirely possible and often embarrassingly easy to accomplish.

Lean manufacturing defines seven wastes that can be optimized out of a process.

- Overproduction: Simply, making more than you currently have demand for. This is a really common mistake for first time producers.

- Inventory: Storing more than you need to meet production or demand. Nearly every company I’ve worked for has this problem. There is an art to having just enough. Don’t buy one bulk order of 3,000 screws for six months, order 500 screws every month as needed.

- Waiting: Having significant delays between processes. These are things ranging from running out of USB cables to simply having to wait too long for something to arrive on a conveyor belt. Do everything you can to make sure the process is always flowing from one step to another.

- Motion: If you have a person walking back and forth between the ends of the factory to complete one step of the manufacturing process, this is wasted motion.

- Transport: Different from motion, this is waste in moving the products of each individual process between sections of the assembly.

- Rework: Get it right the first time. If your process can’t produce a product that meets specifications, fix the process.

- Over-processing: Don’t do more work than is necessary. If your part specifies 1000 hours of runtime don’t buy a million dollar machine to get 2000 hours out of it. If you can find a way to do it with one step, don’t do it with three.

The first thing that stuck out to me upon entering Othermachine Co’s shop floor is their meticulous system for getting small batches through the factory in a timely manner. This allows them to scale their production as their demand fluctuates. CNCs and 3D printers are definitely seasonal purchases; with sales often increasing in the winter months when hackers are no longer lured away from their workstations by nice weather.

As the seven sins proclaim. It would be a bad move for Othermachine Co. to make too many mills. Let’s say they had made an extra 100 mills while demand was at a seasonal low. If they found a design or quality problem from customer feedback they’d have to commit to rework, potentially throwing away piles of defective parts. If they want to push a change to the machine or release a new model they’d either have to rework the machines, trash them, or wait till they all sold before improving their product. Even worse, they may find themselves twiddling their thumbs waiting for their supply to decrease enough to start manufacturing again. This deprives them of opportunities to improve their process and leads to a lax work environment.

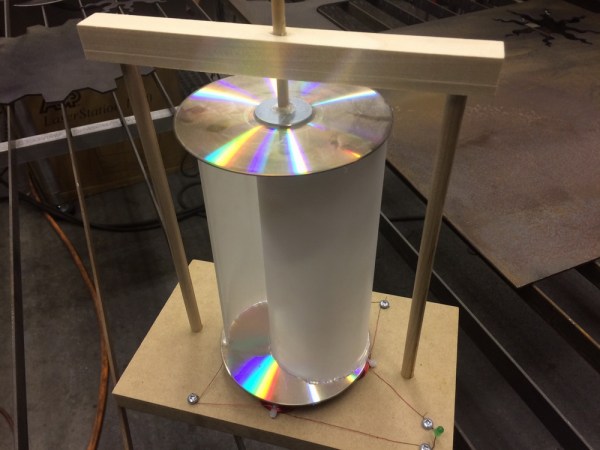

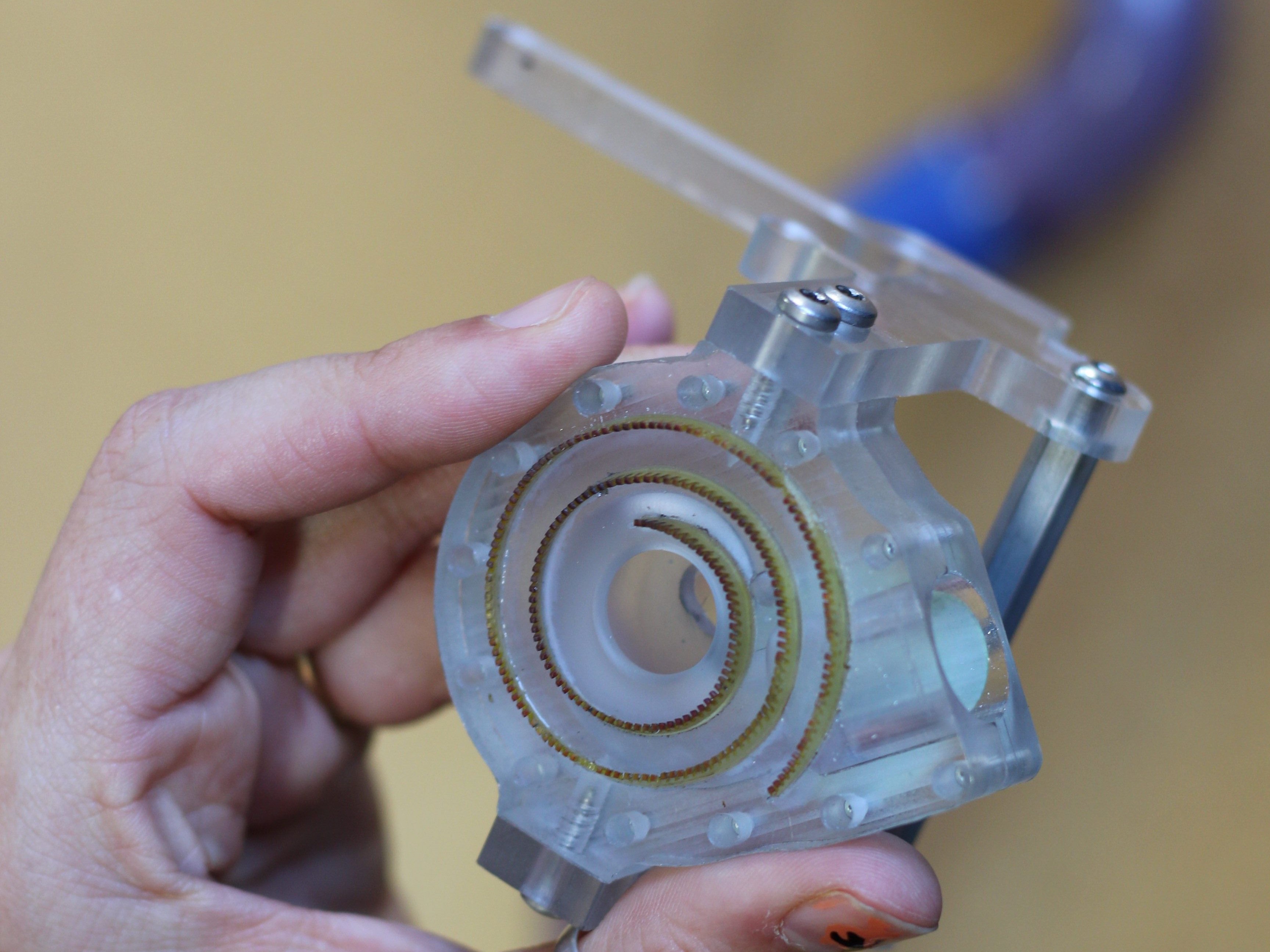

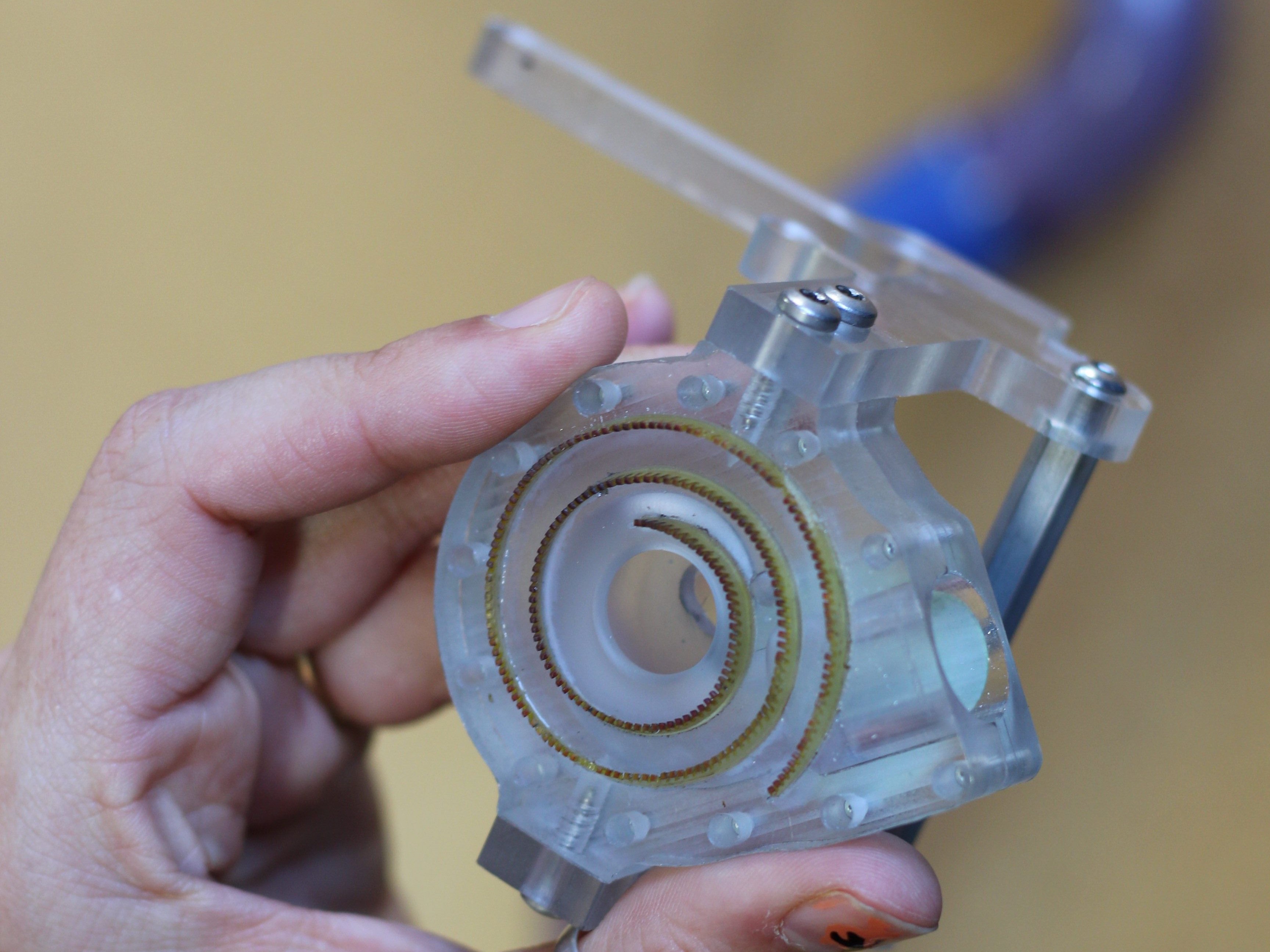

One way to ensure that parts are properly handled and inventory is kept to a minimum is with proper visual controls. To this end, Othermachine Co has custom cardboard bins made that perfectly cradle all the precision parts for each process in their own color coded container. Since the shop floor is quite small, it lets them focus on making spindle assemblies one day and motion assemblies another without having to waste time between each step. Also, someone can rekit the parts for a recently completed step easily without interrupting work on the current process going on.

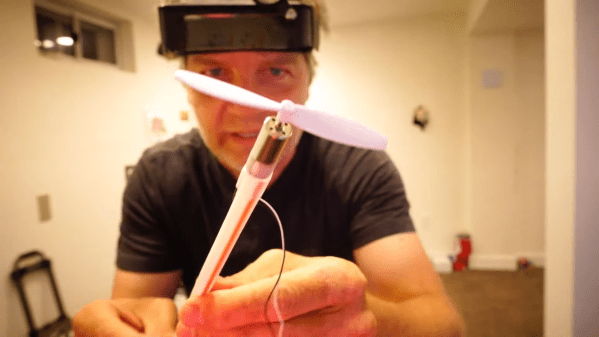

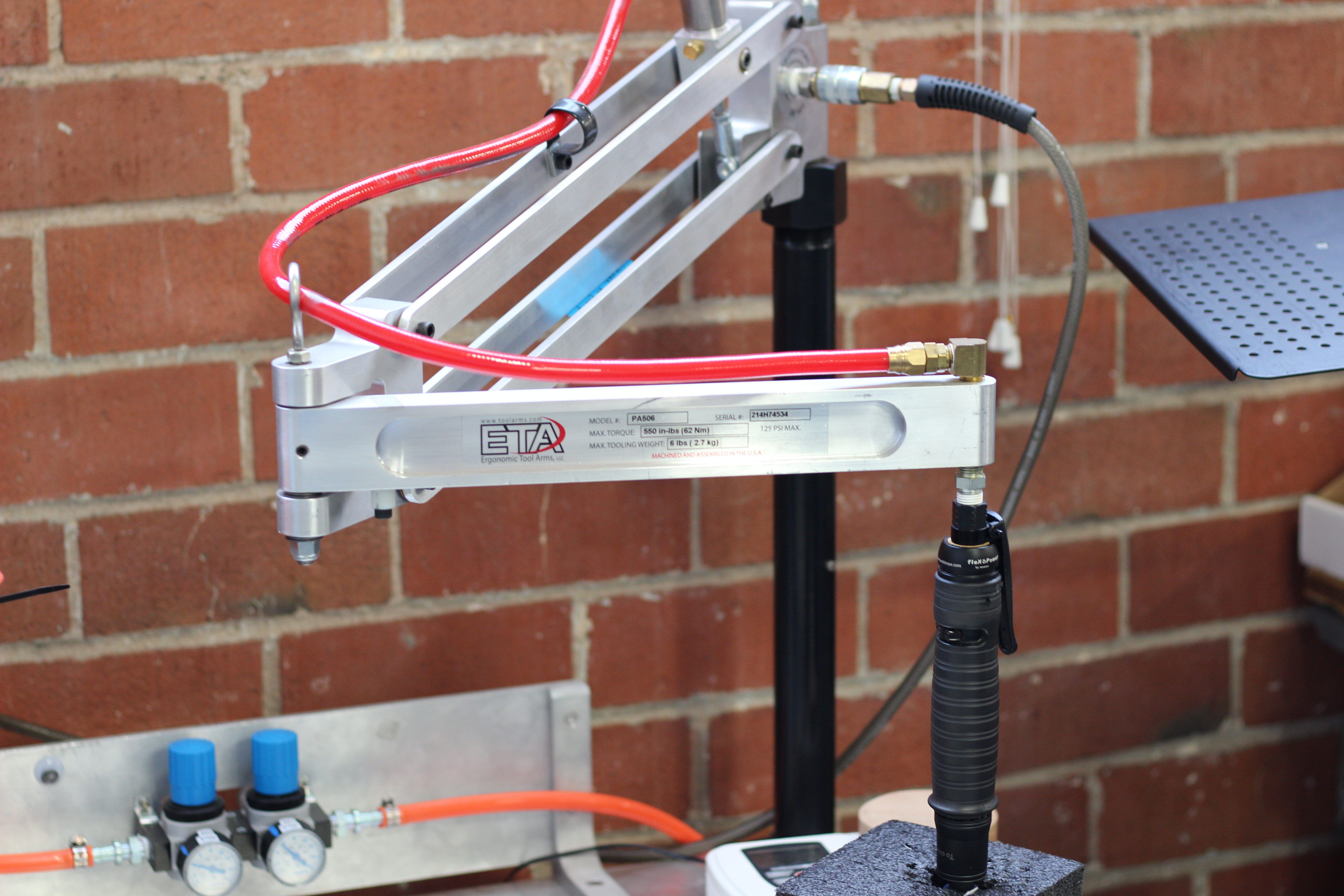

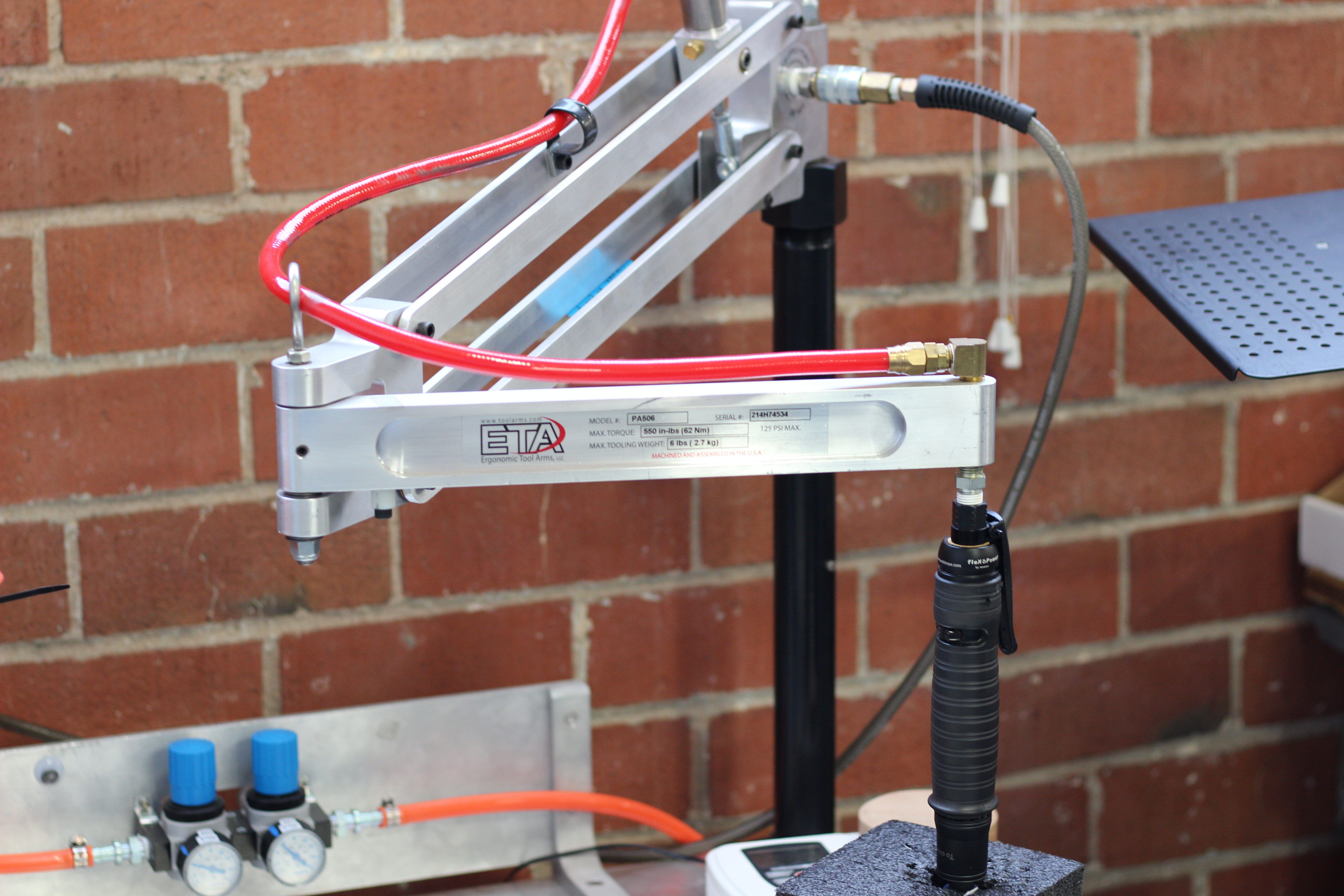

It’s hard to define what’s over processing and what isn’t. My favorite example of what isnt, and something I’ve fought for on nearly every factory floor I’ve worked on is proper torque limiting screwdrivers. They’re a little expensive, but they are a wonderful tool that helps to avoid costly rework and over processing. For example, let’s say you didn’t have a torque limiting screwdriver. Maybe your customers would complain that occasionally a screw came loose. Now, one way to solve this would be the liberal application of Loctite. Another way would be an additional inspection step. Both of these are additional and completely uneccessary steps as most screws will hold as long as they are torqued properly.

In one factory I worked in, it was often a problem that a recently hired worker would overtorque a screw, either stripping it or damaging the parts it was mating together. A torque limiting screwdriver takes the worker’s physical strength out of the equation, while reducing their fatigue throughout the day. It’s a win/win. Any time a crucial step can go from unknown to trusted with the application of a proper tool or test step it is worth it.

Another section where Othermachine Co. applied this principle is with the final machining step for the CNC bed. The step produces a large amount of waste chips. Rather than having an employee waste time vacuuming out every Othermill after it has gone through this process, they spent some time designing a custom vacuum attachment. This essentially removed an entire production step. Not bad!

With the proper management of waste it is entirely possible to save money and improve a process at the same time. It takes a bit of training to learn how to see it. It helps to have an experienced person around in order to learn how to properly respond to them, but with a bit of practice it becomes a skill that spreads to all areas of life. Have any of you had experience with this kind of problem solving? I’ve really enjoyed learning from the work stories posted in the comments.