While it’s great to be experienced and have a ton of specialist knowledge needed to solve a problem, there’s something liberating about coming at things from a position of ignorance. Starting at ground zero can lead you down the path less traveled, and reveal solutions that might otherwise not have presented themselves. And, if [Robin Debreuil]’s exploration of the “minimum viable quadcopter” is any example, some pretty fun failure modes too.

The minimum viable product concept is nothing new of course, being a core concept in Lean methodologies and a common practice in many different industries. The idea of building an MVP is to get something working and in the hands of users, who will then give you feedback on everything wrong with it, plus, if you’re lucky, what you got right. That feedback informs the next design, which leads to more feedback and a whole iterative process that should design the perfect widget.

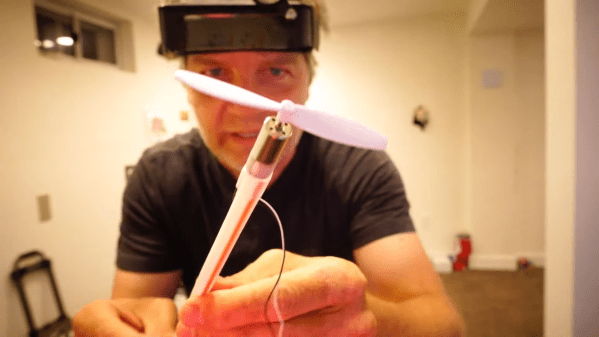

In [Robin]’s case, he wanted to build a quadcopter, but didn’t know where to start. So his first version was as simple as possible: a motor with a propellor and a small LiPo battery. No chassis, no control electronics — nothing. And it worked just about as well as expected. But fixing that problem led to different designs, the process of which was fascinating — we especially liked the quad with opposing motors controlled by mercury tilt switches to sense attitude changes.

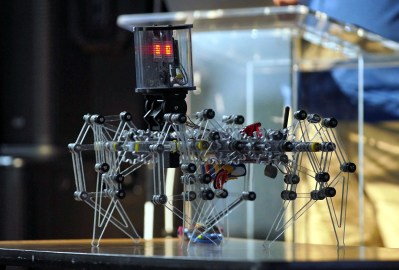

In the end, [Robin] took a more conventional tack and used a microcontroller and BetaFlight to get his popsicle stick and hot glue UAV airborne. But the decision to start with a minimum viable design and iterate from there was a powerful learning experience in tune with [Robin]’s off-beat and low-key outlook, which we’ve seen before with his use of bismuth for desoldering and his scratch-off PCBs.

Continue reading “Minimum Viable Quad Build Shows What Starting From Nothing Can Accomplish”