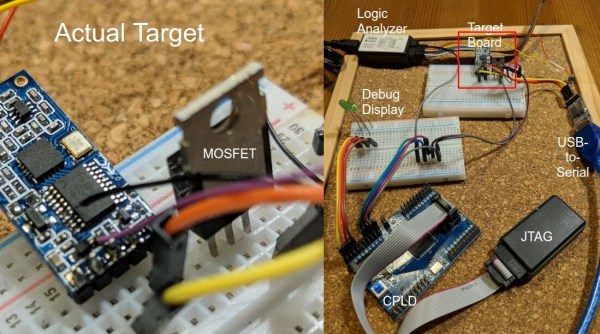

[aleaksah] got himself a Mi Smart Kettle Pro, a kettle with Bluetooth connectivity, and a smartphone app to go with it. Despite all the smarts, it couldn’t be turned on remotely. Energized with his vision of an ideal smart home where he can turn the kettle on in the morning right as he wakes up, he set out to right this injustice. (Russian, translated) First, he tore the kettle down, intending to dump the firmware, modify it, and flash it back. Sounds simple enough — where’s the catch?

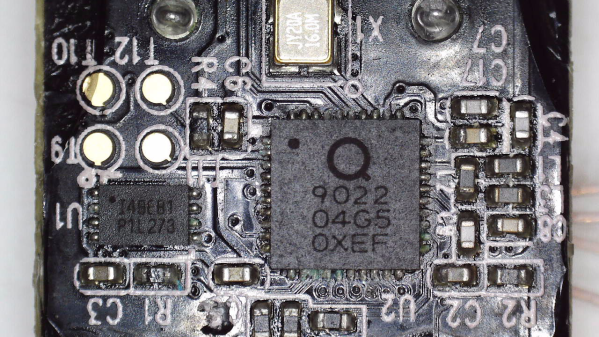

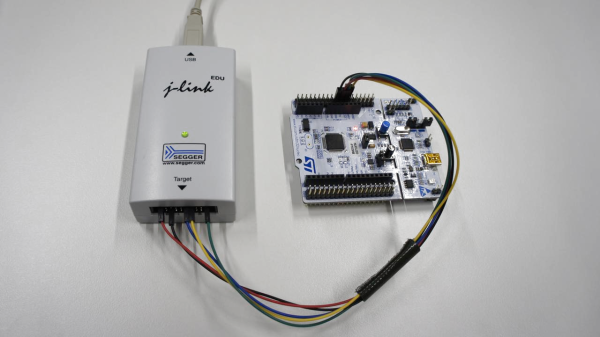

This kettle is built around the QN9022 controller, from the fairly open QN902X family of chips. QN9022 requires an external SPI flash chip for code, as opposed to its siblings QN9020 and QN9021 which have internal flash akin to ESP8285. You’d think dumping the firmware would just be a matter of reading that flash, but the firmware is encrypted at rest, with a key unique to each MCU and stored internally. As microcontroller reads the flash chip contents, they’re decrypted transparently before being executed. So, some other way had to be found, involving the MCU itself as the only entity with access to the decryption key.

Continue reading “Dumping Encrypted-At-Rest Firmware Of Xiaomi Smart Kettle”