As computer hardware gets better and better, most of the benefits are readily apparent to users. Faster processors, less power consumption, and lower cost are the general themes here. But sometimes increased performance comes with some unusual downsides. A research group at the University of California, Irvine found that high-performance mice have such good resolution that they can be used to spy on a user’s speech or other sounds around them.

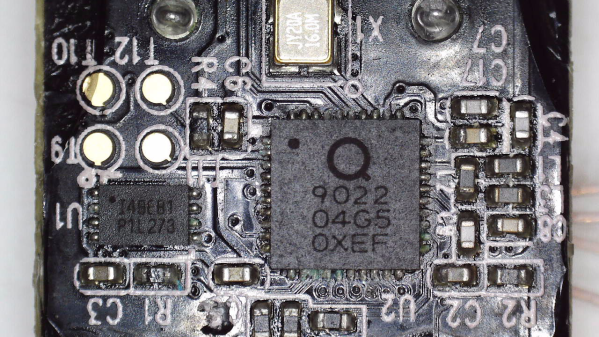

The mice involved in this theoretical attack need to be in the neighborhood of 20,000 dpi, as well as having a relatively high sampling rate. With this combination it’s possible to sense detail fine enough to resolve speech from the vibrations of the mouse pad. Not only that, but the researchers noted that this also enables motion tracking of people in the immediate vicinity as the vibrations caused by walking can also be decoded. The attack does require a piece of malware to be installed somewhere on the computer, but the group also theorize that this could easily be done since most security suites don’t think of mouse input data as particularly valuable or vulnerable.

Even with the data from the mouse, an attacker needs a sophisticated software suite to be able to decode and filter the data to extract sounds, and the research team could only extract around 60% of the audio under the best conditions. The full paper is available here as well. That being said, mice will only get better from here so this is certainly something to keep an eye on. Mice aren’t the only peripherials that have roundabout attacks like this, either.

Thanks to [Stephen] for the tip!