Ever wondered if you could build a robot controlled by chemical reactions? [Marb] explores this wild concept in his video, merging chemistry and robotics in a way that feels straight out of sci-fi. From glowing luminol reactions to creating artificial logic gates, [Marb]—a self-proclaimed tinkerer—takes us step-by-step through crafting the building blocks for what might be the simplest form of a chemical brain.

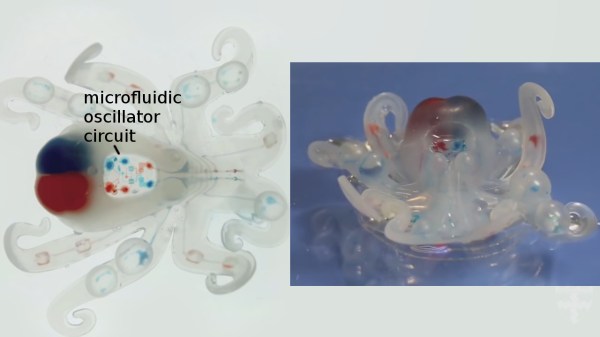

In this video, the possibilities of an artificial chemical brain take centre stage. It starts with chemical reactions, including a fascinating luminol-based clock reaction that acts as a timer. Then, a bionic robot hand makes its debut, complete with a customised interface bridging the chemical and robotic worlds. The highlight? Watching that robotic hand respond to chemical reactions!

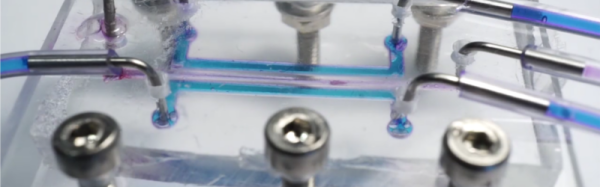

The project relies on a “lab-on-a-chip” approach, where microfluidics streamline the processes. Luminol isn’t just for forensic TV shows anymore—it’s the star of this experiment, with resources like this detailed explanation breaking down the chemistry. For further reading, New Scientist has you covered.

We’ve had interesting articles on mapping the human brain before, one on how exactly brains might work, or even the design of a tiny robot brain. Food for thought, or in other words: stirring the gray matter.

Continue reading “Gray Matter On A Chip: Building An Artificial Brain With Luminol”