Commercial industrial agriculture is responsible for providing food to the world’s population at an incredibly low cost, especially when compared to most of human history when most or a majority of people would have been involved in agriculture. Now it’s a tiny fraction of humans that need to grow food, while the rest can spend their time in cities and towns largely divorced from needing to produce their own food to survive. But industrial agriculture isn’t without its downsides. Providing inexpensive food to the masses often involves farming practices that are damaging to the environment, whether that’s spreading huge amounts of synthetic, non-renewable fertilizers or blanket spraying crops with pesticides and herbicides. [NathanBuildsDIY] is tackling the latter problem, using an automated drone system to systemically target weeds to reduce his herbicide use.

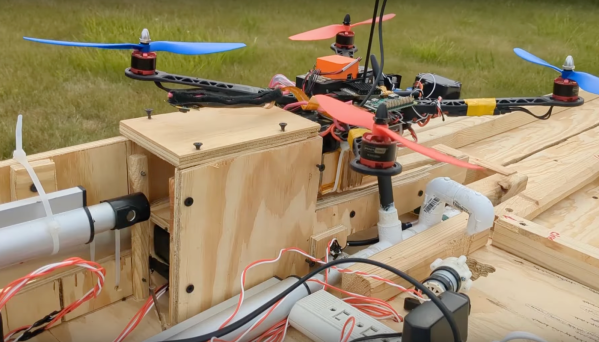

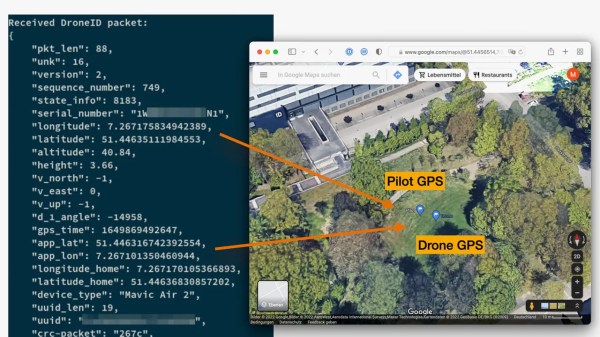

The specific issue that [NathanBuildsDIY] is faced with is an invasive blackberry that is taking over one of his fields. To take care of this issue, he set up a drone with a camera and image recognition software which can autonomously fly over the field thanks to Ardupilot and a LiDAR system, differentiate the blackberry weeds from other non-harmful plants, and give them a spray of herbicide. Since drones can’t fly indefinitely, he’s also build an automated landing pad complete with a battery swap and recharge station, which allows the drone to fly essentially until it is turned off and uses a minimum of herbicide in the process.

The entire setup, including drone and landing pad, was purchased for less than $2000 and largely open-source, which makes it accessible for even small-scale farmers. A depressing trend in farming is that the tools to make the work profitable are often only attainable for the largest, most corporate of farms. But a system like this is much more feasible for those working on a smaller scale and the automation easily frees up time that the farmer can use for other work. There are other ways of automating farm work besides using drones, though. Take a look at this open-source robotics platform that drives its way around the farm instead of flying.

Thanks to [PuceBaboon] for the tip!