Perhaps no words fill me with more dread than, “I hear there’s something going around.” In my experience, you hear this when some nasty bug has worked its way into the community and people start getting whatever it is. I’m always on my guard when I hear about something like this, especially when it’s something really unpleasant like norovirus. Forewarned is forearmed, after all.

Since I work from home and rarely get out, one of the principal ways I keep apprised of what’s going on with public health in my community is by listening to my scanner radio. I have the local fire rescue frequencies programmed in, and if “there’s something going around,” I usually find out about it there first; after a half-dozen or so calls for people complaining of nausea and vomiting, you get the idea it’s best to hunker down for a while.

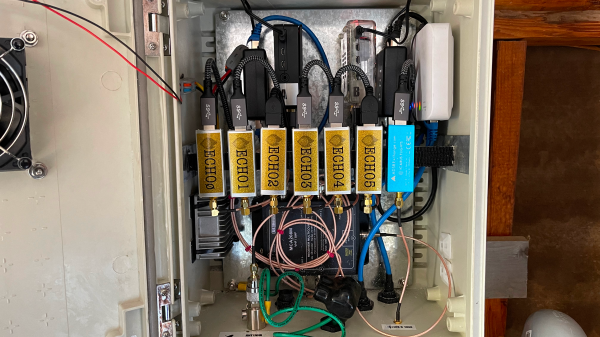

I manage to stay reasonably well-informed in this way, but it’s not like I can listen to my scanner every minute of the day. That’s why I was really excited when my friend Mark Hughes started a project he called Boondock Echo, which aims to change the two-way radio communications user experience by enabling internet-backed recording and playback. It sounded like the perfect system for me — something that would let my scanner work for me, instead of the other way around. And so when Mark asked me to participate in the beta test, I jumped at the chance.