Those who indulge in trading card games know that building the best deck is the key to victory. What exactly that entails is a mystery to us muggles, but keeping track of your cards is a vital part of the process, one that this DIY card scanner (original German; English translation) seeks to automate.

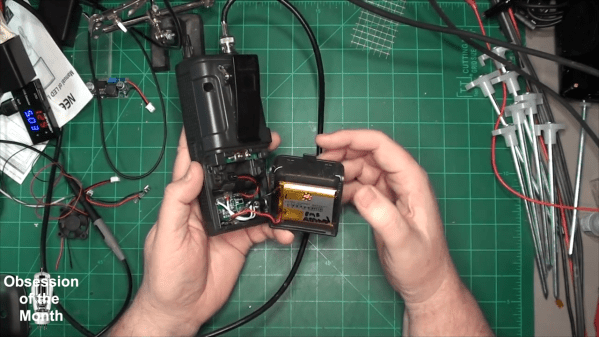

At its heart, [Fraens]’ card scanner is all about paper handling, which is always an engineering task fraught with peril. Cards like those for Magic: The Gathering and other TCGs are meant to be handled by human hands, and automating the task of flipping through them presents some challenges. [Fraens] uses a pair of motorized 3D-printed rollers with O-rings to form a conveyor belt that can pull one card at a time off the bottom of a deck. An adjustable retaining roller made from the most adorable linear bearing we’ve ever seen ensures that only one card at a time is pulled from the hopper onto an imaging platen. An adjustable mount holds a smartphone to take a picture of the card, which is fed into an app that extracts all the details and categorizes the cards in the deck.

Aside from the card handling mechanism, there are some pretty slick details to this build. The first is that [Fraens] noticed that the glossy finish on some cards interfered with scanning, leading him to add a diffused LED ringlight to the rig. If an image isn’t scannable, the light goes through a process of dimming and switching colors until a good scan is achieved. Also, to avoid the need to modify the existing TCG deck management app, [Fraens] added a microphone to the control side of the scanner that listens for the sounds the app makes when it scans cards. And if Magic isn’t your thing, the basic mechanism could easily be modified to scan everything from business cards to old family photos.

Continue reading “3D-Printed Scanner Automates Deck Management For Trading Card Gamers”

![The film scanner [xssfox] found, in the center of a table, with other stuff strewn across the table](https://hackaday.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/hadimg_iscsi_scanner_feat.png?w=600&h=450)