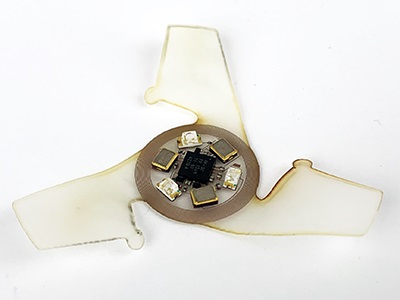

Researchers at Northwestern University is moving the goalposts on how small you can make a tiny flying object down to 0.5 mm, effectively creating flying microchips. Although “falling with style” is probably a more accurate description.

Like similar projects we featured before from the Singapore University of Technology and Design, these tiny gliders are inspired by the “helicopter seeds” produced by various tree species. They consist of a single shape memory polymer substrate, with circuitry consisting of silicon nanomembrane transistors and chromium/gold interconnects transferred onto it.

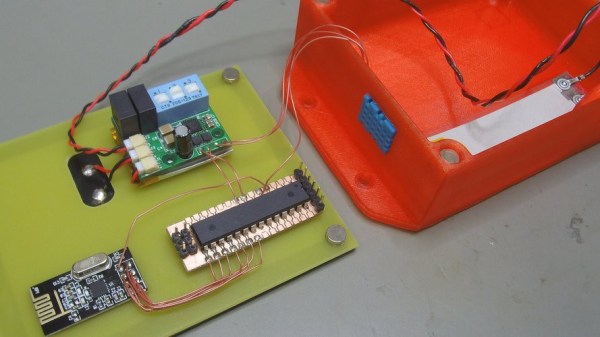

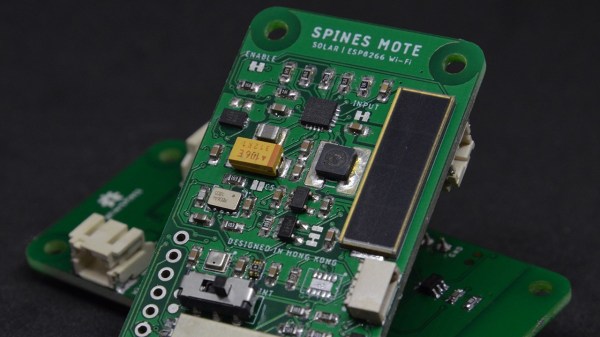

Looking at the research paper, it appears that the focus at this stage was mainly on the aerodynamics and manufacturing process, rather than creating functional circuitry. A larger “IoT Macroflyer” did include normal ICs, which charges a super capacitor from a set of photodiodes operating in the UV-A spectrum, which acts as a cumulative dosimeter. The results of which can be read via NFC after recovery.

As with other similar projects, the proposed use-cases include environmental monitoring and surveillance. Air-dropping a large quantity of these devices over the landscape would constitute a rather serious act of pollution, for which case the researchers have also created a biodegradable version. Although we regard these “airdropped sensor swarms” with a healthy amount of skepticism and trepidation, we suspect that they will probably be used at some point in the future. We just hope that those responsible would have considered all the possible consequences.