In Al Williams’s marvelous rant he points out a number of the problems with speaking to computers. Obvious problems with voice control include things like multiple people talking over each other, discerning commands from background conversations, and so on. Somehow, unlike on the bridge in Star Trek, where the computer seems to understand everyone just fine, Al sometimes can’t even get the darn thing to play his going-to-sleep playlist, which should be well within the device’s capabilities.

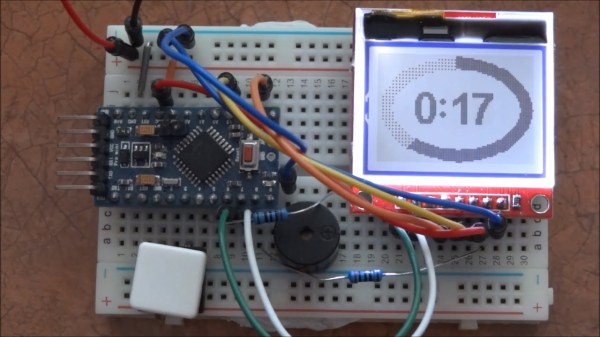

In the comments, [rclark] suggests making a single button that plays his playlist, no voice interaction required, and we have to admit that it’s a great solution to this one particular problem. Heck, the “bedtime button” would make fun project in and of itself, and it’s such a limited scope that it could probably only be an weekend’s work for anyone who has touched the internals of their home automation system, like Al certainly has. We love the simplicity of the idea.

But it ignores the biggest potential benefit of a voice control system: that it’s a one-size-fits-all solution for everything. Imagine how many other use cases Al would need to make a single button device for, and how many coin cell batteries he’d be signing himself up to change out over the course of the year. The trade-off is that the general purpose solution tends not to be as robust as a single-tasker like the button, but also that it can potentially simplify the overall system.

I suffer this in my own home. It’s much more a loosely-coupled web of individual hacks than an overall system, and that has pros and cons. Each individual part is easier to maintain and hack on, but the overall system is less coordinated than it could be. If we change the WiFi password on the home automation router, for instance, I’m going to have to individually log into about eight ESP8266s and change their credentials. Yuck!

It’s probably a matter of preference, but I’ll still take the loose, MQTT-based system that I’ve got now over an all-in-one. Like [rclark], I value individual device simplicity and reliability above the overall system’s simplicity, but because our stereo isn’t even hooked up to the network, I can’t play myself to sleep like Al can. Or at least like he can when the voice recognition is working.