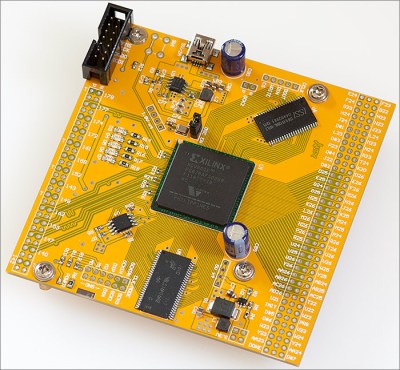

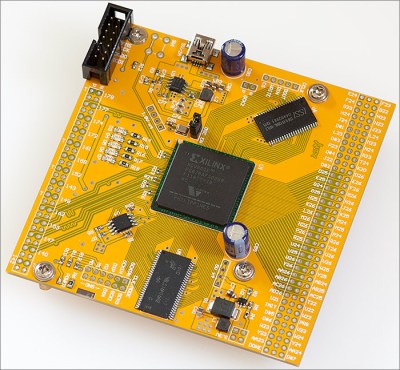

One day [Andy] was cruising around eBay and spotted something interesting. Forty Virtex-E FPGAs for two quid each. These are the big boys of the FPGA world, with 512 user IO pins, almost 200,000 logic gates, packed into a 676-ball BGA package. These are not chips designed for the hobbyist. These chips are not designed for boards with less than six layers. These chips aren’t even designed for boards with 6/6mil tolerances from the usual suspects in China. By any account, a 676-ball package is not like a big keep out sign for hobbyists. You don’t turn down a £2 class in advanced PCB design, though, leading to one of the most impressive ‘I just bought some crap on eBay’ projects we’ve seen.

The project [Andy] had in mind for these chips was a generic dev board, which meant breaking out the IO pins and connecting some SRAM, SDRAM, and Flash memory. The first issue with this project is escape routing all the balls. Xilinx published a handy application note that recommends specific design parameters for the traces of copper under the chip. Unfortunately, this was a six-layer board, and the design rules in the application note were for 5/5mil traces. [Andy]’s board house can’t do six-layer boards, and their design rules are for 6/6mil traces. To solve this problem, [Andy] just didn’t route the inner balls, and hoped the 5mil traces would work out.

The project [Andy] had in mind for these chips was a generic dev board, which meant breaking out the IO pins and connecting some SRAM, SDRAM, and Flash memory. The first issue with this project is escape routing all the balls. Xilinx published a handy application note that recommends specific design parameters for the traces of copper under the chip. Unfortunately, this was a six-layer board, and the design rules in the application note were for 5/5mil traces. [Andy]’s board house can’t do six-layer boards, and their design rules are for 6/6mil traces. To solve this problem, [Andy] just didn’t route the inner balls, and hoped the 5mil traces would work out.

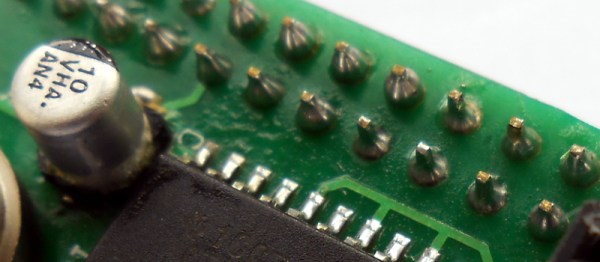

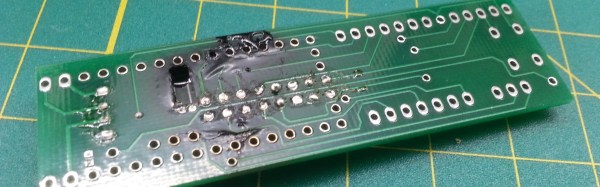

With 676 tiny little pads on a PCB, the clocks routed, power supply implemented, too many decoupling caps on the back, differential pairs, static RAM, a few LEDs placed just for fun, [Andy] had to solder this thing up. Since the FPGA was oddly one of the less expensive items on the BOM, he soldered that first, just to see if it would work. It did, which meant it was time to place the RAM, Flash, and dozens of decoupling caps. Everything went relatively smoothly – the only problem was the tiny 0402 decoupling caps on the back of the board. This was, by far, the hardest part of the board to solder. [Andy] only managed to get most of the decoupling caps on with a hot air gun. That was good enough to bring the board up, but he’ll have to figure some other way of soldering those caps for the other 30 or so boards.

Continue reading “DIYing Huge BGA Packages” →

The project [Andy] had in mind for these chips was a generic dev board, which meant breaking out the IO pins and connecting some SRAM, SDRAM, and Flash memory. The first issue with this project is escape routing all the balls. Xilinx published a handy application note that recommends specific design parameters for the traces of copper under the chip. Unfortunately, this was a six-layer board, and the design rules in the application note were for 5/5mil traces. [Andy]’s board house can’t do six-layer boards, and their design rules are for 6/6mil traces. To solve this problem, [Andy] just didn’t route the inner balls, and hoped the 5mil traces would work out.

The project [Andy] had in mind for these chips was a generic dev board, which meant breaking out the IO pins and connecting some SRAM, SDRAM, and Flash memory. The first issue with this project is escape routing all the balls. Xilinx published a handy application note that recommends specific design parameters for the traces of copper under the chip. Unfortunately, this was a six-layer board, and the design rules in the application note were for 5/5mil traces. [Andy]’s board house can’t do six-layer boards, and their design rules are for 6/6mil traces. To solve this problem, [Andy] just didn’t route the inner balls, and hoped the 5mil traces would work out.