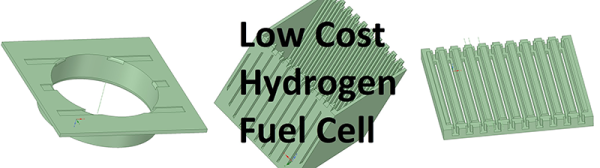

Electronic cars and planes are the wave of the future, or so we’re told, but if you do the math on power densities, the future looks bleak. Outside of nuclear power, you can’t beat the power density of liquid hydrocarbons, and batteries are terrible stores of energy. How then do we tap the potential of high density fuels while still being environmentally friendly? With [Lloyd]’s project for The Hackaday Prize, a low cost hydrogen fuel cell.

Traditionally, fuel cells have required expensive platinum electrodes to turn hydrogen and oxygen into steam and electricity. Recent advances in nanotechnology mean these electrodes may be able to be produced at a very low cost.

For his experiments, [Lloyd] is using sulfonated para-aramids – Kevlar cloth, really – for the proton carrier of the fuel cell. The active layer is made from asphaltenes, a waste product from tar sand extraction. Unlike platinum, the materials that go into this fuel cell are relatively inexpensive.

[Lloyd]’s fuel cell can fit in the palm of his hand, and is predicted to output 20A at 18V. That’s doesn’t include the tanks for supplying hydrogen or any of the other system ephemera, but it is an incredible amount of energy in a small package.

You can check out [Lloyd]’s video for the Hackaday Prize below.

Continue reading “Hackaday Prize Semifinalist: A Low Cost, DIY Fuel Cell”