Some of the more interesting consumer hardware devices of recent years have been smart glasses. Devices like Google Glass or Snapchat Spectacles, eyewear incorporating a display and computing power to deliver information or provide augmented reality on an unobtrusive wearable platform.

Raspberry Pi Zero Smart Glass aims to provide an entry into this world, with image recognition and OCR text recognition in a pair of glasses courtesy of a Raspberry Pi Zero. Unusually though it does not take the display option of other devices of having a mirror or prism in the user’s field of view, instead it replaces the user’s entire field of view with a display and re-connects them to the world through the Raspberry Pi camera.

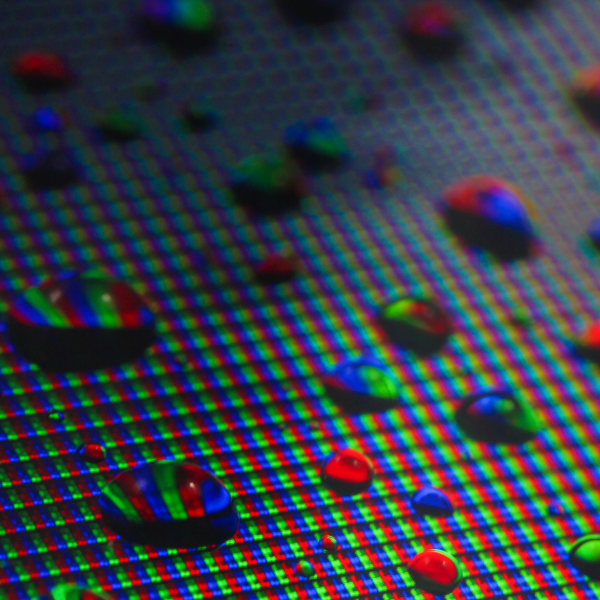

The display in question is an inexpensive set of “3D Virtual Stereo Digital Video glasses”, of the type that can be found fairly easily on your favourite auction site. They aren’t particularly high-resolution, but the Pi can easily drive them with its composite video output. The electronics and camera are mounted on a headband, in a custom 3D-printed enclosure. All files can be downloaded from the project page.

There is some Python software, but it’s fair to say that there is not a clear demo on the project page showing it working. However this is no reason to disregard this project, because even if its software has yet to achieve its full potential there is value elsewhere. The 3D-printed Raspberry Pi enclosure should be of use to many other similar wearable projects, and we’d almost say it’s worthy of a project all of its own.