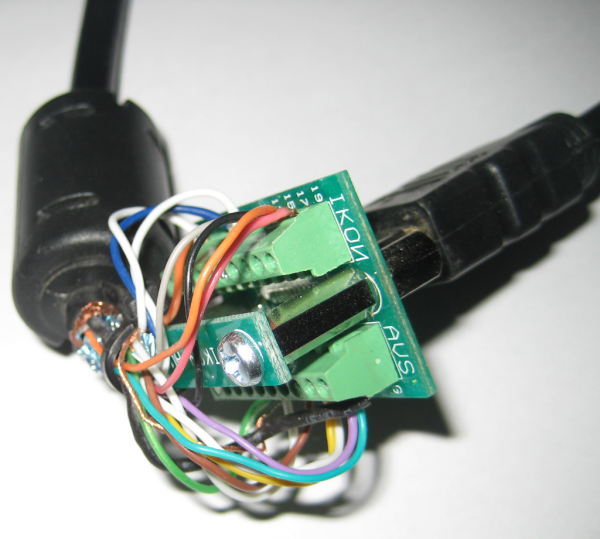

There’s two really useful parts to this hack which involves sniffing the HDMI protocol’s HDCP security keys. The first is just getting at the signals without disrupting communications between two HDCP capable devices. To do so [Adam Laurie] started by building an HDMI breakout cable that also serves as a pass-through. The board seen above is known as an HDMI screw terminal board. The image shows one cable connecting to itself during the fabrication process. What he did was cut one end off of an HDMI cable, then used a continuity tester to figure out which screw terminal connects with which bare wire. After all the wires are accounted for the end with the plug goes to his TV, with a second cable connecting between the board’s socket and his DVD player.

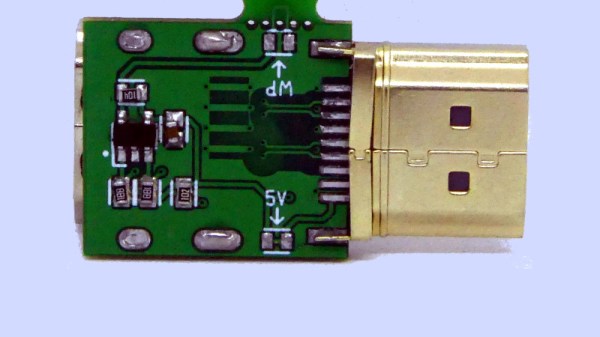

The rest of his post is dedicated to sniffing the security keys. His weapon of choice on this adventure turns out to be a Bus Pirate but it runs a little slow to capture all of the data. He switches to a tool of his own design, which runs on a 60MHz PIC32 demo board. With it he’s able to get the keys which make decrypting the protected data possible.