The more accomplished 8-bit microcomputers of the late 1970s and early 1980s had a dedicated display chip, a CRT controller. This took care of all the jobs associated with driving a CRT display, generating the required timing and sequencing all the dots to make a raster. With a CRT controller on hand the CPU had plenty of time to do other work, but on some cheaper machines there was no CRT controller and the processor had to do all the work of assembling the display itself.

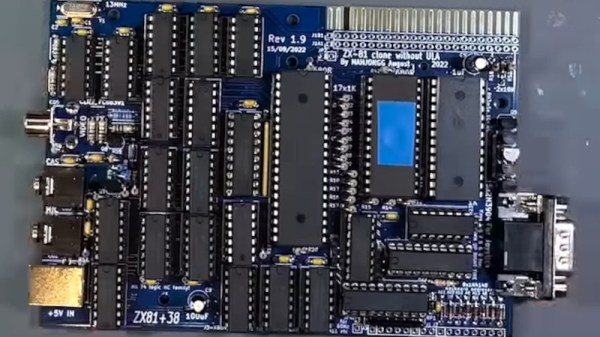

[Dr. Matt Regan] had a Sinclair ZX81 which relied on this technique, and he’s put up the first of what will become a series of videos offering a deep dive into this method of creating video. The key to its operation lies in very careful use of timing, with operations executed to keep a consistent number of clock cycles per dot on the display. He’s making a very low resolution version of the display in the first video, which he manages to do with only an EPROM and a couple of 74 logic chips alongside the Z80. We’re particularly impressed with the means of creating the sync pulses, using opcodes carefully chosen to do nothing of substance except setting a particular bit.

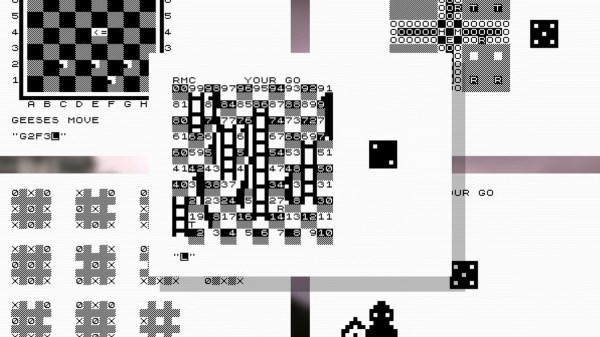

This method of assembling a display on such a relatively slow microprocessor has the drawback of no means of creating a grayscale, and of course it’s only available in glorious black and white. But it’s the system which gave a first experience of computing to millions, and for that we find the video fascinating. Take a look, below the break.

If this has caused you to yearn for all things Sinclair, read our tribute to the man himself.