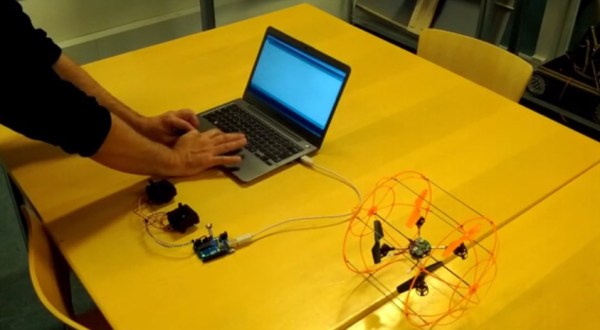

Building your own quadcopter is an expensive and delicate ordeal. Only after you navigate a slew of different project builds do you feel confident enough to start buying parts, and the investment may not be worth your effort if your goal is to jump right into some hacking. Fortunately, [Dzl] has a shortcut for us; he reverse engineered the communication protocol for a cheap toy quadcopter to work with an Arduino.

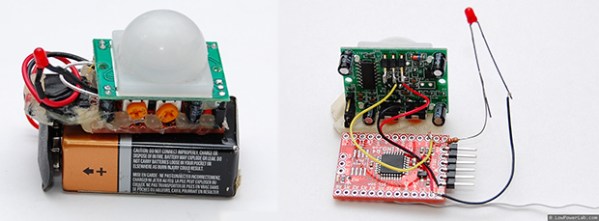

The cheap toy in question is this one from Hobbyking, which you can see flying around in their product demonstration video. [Dzl] cracked open the accompanying control handset to discover which transceiver it used, then found the relevant datasheet and worked out all the pin configuration involved in the SPI communication. Flying data is transmitted as 8 byte packets sent every 20 mS, controlling the throttle, yaw, pitch and roll.

[Dzl] took the build a step further, writing an Arduino library (direct Dropbox download link) that should catch you up to speed and allow you to skip straight to the fun part: hacking and experimenting! See his quick video after the break, then convince yourself you need a quadcopter by watching this one save its creator, [Paul], the trouble of walking his son to the bus stop.

Continue reading “Hacking A Cheap Toy Quadcopter To Work With Arduino”