Learn the ins and outs of multi-core microcontrollers as Chip Gracey leads this week’s Hack Chat on Friday 5/5 at noon PDT. Chip founded Parallax and has now been working for more than a decade on the Propeller 2 design, a microcontroller which has 8 and 16 core options.

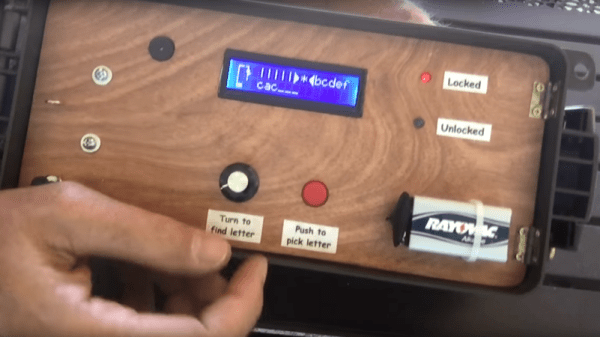

When it comes to embedded development, most people think of a single process running. Doing more than one task at a time is an illusion provided by interrupts that stop one part of your program to spend a few cycles on another part before returning. The Propeller 2 has true parallel processing; each core can run its own part of the program. From the embedded engineer’s perspective that makes multiple real-time operations possible. Where things get really interesting is how those cores work together.

When it comes to embedded development, most people think of a single process running. Doing more than one task at a time is an illusion provided by interrupts that stop one part of your program to spend a few cycles on another part before returning. The Propeller 2 has true parallel processing; each core can run its own part of the program. From the embedded engineer’s perspective that makes multiple real-time operations possible. Where things get really interesting is how those cores work together.

Here’s your chance to hear about multi-core embedded first hand, from both the silicon design side and the firmware developer side. Join us for a Parallax Hack Chat this Friday at noon PDT.

Here’s How To Take Part:

Our Hack Chats are live community events on the Hackaday.io Hack Chat group messaging.

Our Hack Chats are live community events on the Hackaday.io Hack Chat group messaging.

Log into Hackaday.io, visit that page, and look for the ‘Join this Project’ Button. Once you’re part of the project, the button will change to ‘Team Messaging’, which takes you directly to the Hack Chat.

You don’t have to wait until Friday; join whenever you want and you can see what the community is talking about.