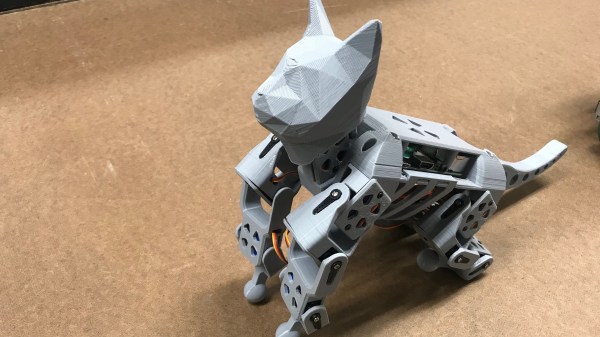

SmallKat is a cute little robot with a lot of capability designed around teaching and experimenting with dynamic robot control. It’s a shame we haven’t covered SmallKat yet, as it’s both a finalist in the 2019 Hackaday Prize and was one of the Bootstrap Winners this year.

Many hobby robots move by repeating a pre-programmed sequence of movements. Most hexapods for example follow this line of thought. However, robots like Spot and the MiniCheetah show a different world where robots determine the locations of their limbs by their current state, the measured state of their environment, and some imagined future. These robots are capable of so much more than their predecessors.

However, even a cost-effective version of these robots climb into the tens of thousands of dollars at a steep curve. SmallKat will help there: based around hobby servos and an ESP32 the hardware stays affordable. Data can be streamed to a much larger computer for experimentation which saves on some of the weight that supporting a larger device like a Pi would add.

This device will let students experiment with all kinds of dynamic models and even machine learning-based movements without breaking the bank. There’s even a nice software studio for experimentation to aid in the learning process. Video of it shuffling around after the break.