Well, this is it. The end of the decade. In a few days the 2010s will be behind us, and a lot of very smug people will start making jokes on social media about how we’re back in the “Roaring 20s” again. Only this time around there’s a lot more plastic, and drastically less bathtub gin. It’s still unclear as to how much jazz will be involved.

Around this time we always say the same thing, but once again it bears repeating: it’s been a fantastic year for Hackaday. Of course, we had our usual honor of featuring literally thousands of incredible creations from the hacking and making community. But beyond that, we also bore witness to some fascinating tech trends, moments that could legitimately be called historic, and a fair number of blunders which won’t soon be forgotten. In fact, this year we’ve covered a wider breadth of topics than ever before, and judging by the record setting numbers we’ve seen in response, it seems you’ve been just as excited to read it as we were to write it.

To close out the year, let’s take a look at a few of the most popular and interesting stories of 2019. It’s been a wild ride, and we can’t wait to do it all over again in 2020.

A Bevy of New Boards

In June we saw the somewhat surprising release of the Raspberry Pi 4. Not that anyone doubted there would be a new entry into this monstrously popular (to the tune of 30 million units, apparently) line of Linux Single Board Computers (SBCs), of course. The surprise was in the timing: the Pi 3B+ had just been released in 2018, and in interviews conducted only a few months prior, Eben Upton was pretty noncommittal about the foundation’s plans for a successor.

As it turns out, this Pi might have needed a bit more time in the oven. After hackers started getting their hands on them, they started finding some pretty odd quirks. We’re not just talking about the (still baffling) decision to use dual micro HDMI ports either. There’s enough legitimate gripes around 2019’s Pi that many are sticking with the previous iteration until things settle down.

But the Raspberry Pi isn’t the only SBC game in town. It’s not even the only one with a cute “Pi” name, for that matter. We saw significant interest in the Atomic Pi, which delivered the power of a quad-core Intel Atom processor at a size and price not far from that of its berry-flavored peer. We’ve since featured a number of impressive modifications to the powerful board, but the discovery that the Atomic Pi was actually surplus hardware purchased from the now defunct Mayfield Robotics raised some valid questions about the long-term viability of the product.

Of course, no piece of hardware got us quite as excited as this year’s Hackaday Superconference Badge. Not only because it’s an exceptionally cool conference badge (something there’s no shortage of), but because it represented something of a turning point for FPGA technology. Thanks to a ballooning number of projects, products, and yes conference badges, leveraging FPGAs and to vast improvements to open source toolchains, we’ll look back on 2019 as the year that many hackers got to play with an FPGA for the first time. If the projects that came out of the Badge Hacking competition are any indication, we think they liked it.

Let there Be Light

Despite the perennial interest in such things, the most talked about piece of hardware this year wasn’t a pocket sized Linux computer. It was, if you can believe it, the humble light bulb. Well, more specifically, the state-of-the-art in home lighting technology.

It’s true. As of this writing, our most popular piece of 2019 was Ted Yapo’s phenomenal deep-dive into the occasionally disappointing reality of modern LED bulbs. We’ve all experienced LED bulbs doing dark years (or even decades) before their advertised lifespan is up, and this article aimed to figure out just what keeps killing these 21st century marvels of solid-state illumination.

We also saw considerable concern about the security of so-called “smart” light bulbs, or more accurately, the lack thereof. The discovery that many of these bulbs stored the user’s WiFi credentials in clear-text was made all the worse as we found out just how easy it was to get physical access to the microcontrollers that power the latest generation of Internet connected bulbs.

Which is probably why we also saw an uptick of DIY smart lighting projects this year; if you can’t trust what’s on the market, you might as well build it yourself. The security of such devices is still very much up for debate, but we could say that for a lot of the projects that have graced these pages over the years.

Resin Gets Reasonable

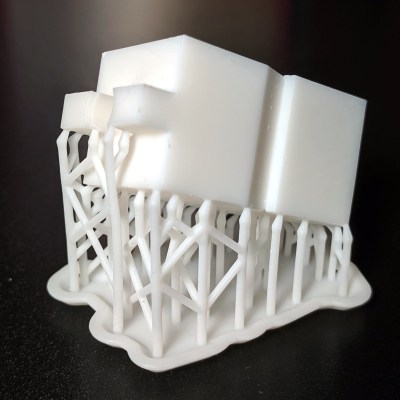

Speaking of light, 2019 will also go down as the year desktop SLA printers finally hit a hacker-friendly price. These printers, which form three dimensional objects out of light-activated resins, are capable of resolutions far beyond what you can do with more traditional FDM machines. Of course top of the line models are still outside the average tinkerer’s budget, but a number of companies are currently offering entry level LCD-based resin printers in the exceptionally enticing $200 to $300 price range.

But buyer beware: even for the 3D printing aficionado, these machines can pose a challenge. Resin printers have their own special quirks and limitations which are wholly different from the quirks and limitations you’ve begrudgingly become accustomed to with FDM printing. As Donald Papp explained in a personal look at his own experiences with a low-cost SLA printer, prospective buyers need to understand what they’re getting into before they trip the light fantastic.

Peeking Inside Alexa

On paper, the hacking community should hate Amazon’s Alexa. A device that connects our homes (and now even cars) to a retail juggernaut would be the kind of thing that, under normal circumstances, we’d terminate with extreme prejudice. But Amazon managed to convince enough of us to install the things that adding Alexa compatibility to gadgets has become a fairly common hack.

But in 2019, we saw what may be the first signs of cracks forming in our tremulous relationship with Amazon’s family of high-tech hockey pucks. There was an incredible amount of interest in the teardown Brian Dorey did on the third generation Echo Dot, as well as his subsequent reverse engineering that revealed the smart speaker had a hidden USB port you could access with a DIY adapter.

But in 2019, we saw what may be the first signs of cracks forming in our tremulous relationship with Amazon’s family of high-tech hockey pucks. There was an incredible amount of interest in the teardown Brian Dorey did on the third generation Echo Dot, as well as his subsequent reverse engineering that revealed the smart speaker had a hidden USB port you could access with a DIY adapter.

We also saw a brilliant hardware add-on that ensures Amazon and Google’s devices are only “assisting” you when you want them to. As hackers, we not only want to know what makes these devices tick, but how to bend them to our will.

Of course, the perception of these gadgets as a security liability certainly wasn’t helped by the fact some madlads managed to whisper sweet nothings to them with laser beams.

Following the New Space Race

For the last couple of years, we’ve had front row seats to a brand new Space Race. But this time it’s not world superpowers seeing who can push higher and farther, this battle is being fought between billionaires like Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, and Richard Branson.

The cost of putting a payload into space is dropping like a stone, to the point that satellite networks with more than 10,000 individual spacecraft are financially viable. NASA’s even trying to get back to the Moon, though it’s still unclear if their lumbering SLS rocket can remain relevant in an era where private industry is making such huge technological leaps.

The cost of putting a payload into space is dropping like a stone, to the point that satellite networks with more than 10,000 individual spacecraft are financially viable. NASA’s even trying to get back to the Moon, though it’s still unclear if their lumbering SLS rocket can remain relevant in an era where private industry is making such huge technological leaps.

SpaceX has all but perfected an engine design that was once considered nearly impossible to build, and they’re currently flying the most powerful rocket in the world. Rocket Lab is putting satellites into orbit using a booster that has an empty weight rivaling a pickup truck. Several companies are working on spacecraft and boosters that can be 3D printed (either on or off world), and they’re a lot closer to demonstrating workable prototypes than you might think.

Make no mistake, space travel is still incredibly difficult and dizzyingly expensive. But there hasn’t been this much activity above our heads since the 1960s, and there’s no sign of things slowing down anytime soon. For those of us who’ve had a lifelong fascination with the final frontier, it’s a very exciting time to be alive.

Boeing’s Very Bad Year

Unfortunately, it hasn’t been a banner year for everyone. Case in point, aerospace giant Boeing. In the century-long history of the legendary company, 2019 will surely be remembered as one of the most publicly embarrassing.

Every 737 MAX aircraft in the world has been grounded since March after it was determined that issues in the plane’s flight control systems were directly responsible for the loss of 346 lives; the longest and costliest grounding of an airliner in United States history. It’s still unknown when the aircraft will be allowed to resume commercial service, but one has to wonder how much consumer confidence will be left when all is said and done. Especially since we now know mechanical failures have been identified in other members of the 737 family.

More recently, the company’s CST-100 Starliner failed to reach the International Space Station during its inaugural flight. It wasn’t a catastrophic failure, and it’s unclear how it will impact NASA’s overall plans to use the Starliner to start ferrying US astronauts to the Station next year, but it’s certainly a very public misstep made all the worse by how effortlessly SpaceX seems to be sailing through similar trials.

All the bad press certainly seemed to get the attention of the Boeing board members. On December 23rd, just one day after the troubled Starliner hobbled its way to an earlier than expected landing in New Mexico, CEO Dennis Muilenburg was fired. Merry Christmas.

The Road Ahead

So what’s in store for us in 2020 and beyond? For one thing, it’s hard to imagine that ARM single board computers are going to make many leaps and bounds in the next 12 months. Even considering all its faults, the Raspberry Pi 4 is still an impressively powerful computer at an incredible size and price; and with the 600 MHz Teensy 4 dropping over the summer, we’d say that microcontroller platforms are also starting to hit a performance plateau. That means hackers will increasingly be pushed towards parallel programming and FPGAs for their high-performance computing needs, so you might as well start learning it now.

We also expect big improvements in battery cost and availability. As if our mobile devices weren’t power hungry enough, every auto manufacturer in the world is scrambling to add electric vehicles to their product lineup. The economies of scale on 18650 cells will only get better, but if we’re really lucky, the demand for high capacity cells with fast recharge times will help spur the development of totally new battery chemistries.

The close of the year is not only the perfect time to reflect on all the incredible things we’ve seen, but also to thank you, the Constant Reader. Without our dedicated audience, we simply couldn’t do the things we do. Whether you’re supplying us with a regular flow of tips from your particular corner of the Internet, attending our live events and meetups, or simply checking in every day and reading what’s new, know that we don’t take it for granted.

There’s no shortage of information on the Internet, and whether you’ve just joined us this year or been around since the very beginning, everyone here at Hackaday is supremely grateful that you’ve decided to make us part of your life.

Now go out there and build something amazing for 2020. We’ll keep an eye out for it.

Actually 2020 is the last year of this decade, not the first of a new decade – people start counting at one not zero…

I’ve always been a fan of zero-indexing. “People” might start counting at 1, but computer engineers start counting at 0.

You’ve just demonstrated the people count in 10 different ways.

Binary. Clever.

I’ll also make an argument in support of 2020 being the last year of the decade. What was the start of the calendar (Gregorian)? The first year = year 1 (immediately following year 1 BC). Ten years wouldn’t have elapsed until the end of the tenth year, year 10. So the second decade started with year 11. Likewise, we won’t enter the 203rd decade until 2021.

The disagreement comes because we didn’t start counting anything at zero until long after the years had been established using the ordinal numbers (first = 1) instead of (first = 0).

However I also agree that in conversation it matters more what that third digit is than how many decades exactly have elapsed. So 1/1/2020 feels more like a milestone than 1/1/2021.

ISO dates please, 2020,01,01. Or star date 20200101. Math maters, numbers in order. Will this year be when people will see clearly and stop saying “and” in the middle of a set of numbers instead of adding them up and just saying the answer?

Echodelta:

I won’t argue that ISO dates make more sense, just as metric and SI units make more sense. But change is hard and never free.

I choose to use the format that will be least confusing (or least likely to be misunderstood) or most useful to whomever is reading, in my estimation. Effective communication is my main goal.

In documents and emails in my daily work that means m/d/yyyy. When naming files it means yyyy.mm.dd so everything is in chronological order.

My apologies if my date formatting was confusing for you.

echodelta: you talk about ISO dates but then use a comma between the numbers when the standard clearly defines the use of a dash.

i prefer ISO 8601

2019-12-29

It is currently the twenty _first_ century, and thus by extension 2020 _is_ the first year of the next decade.

Your logic is faulty, there is no such extension. We start counting at one so ten is the last of the decade, similarly for twenty being the last of the second decade and so on through centuries and millennia. The 21st century therefore ends in 2100 just the same as the 20th century ended in 2000. There are laws in most countries to confirm it. Suggest you do some research…

well, having been a C then C++ programmer for 40 years or so, I can assure you that I always start counting from 0… But yes, retrospectively with our current calendar, there is no year 0…. Clearly no C programmers around when we came up with this scheme..

Nicely summarized the Year 2019.

Keep up with the awesome content HACKADAY

Most of us start to count age at 0. When we come to 1 we have lived 1 year. When we come to 10 we have lived 10 years and started on our 11’th year. Thats how I see it.

Exactly!

2019-12-31 is the last day of the year, the last day of the decade.

2020-01-01 is the first day of the first year of the new decade.

How hard is that to understand?

Right so if I borrow $10 off you, I only need to give you back $9 because the 10th dollar doesn’t actually belong to that $10 but the next $10.

Now you’re just being annoying.

It’s not hard to understand.

But think again of this:

Starting with year 1 (back in the day they didn’t start with year 0), the first decade would end when? After 10 years had elapsed (otherwise it doesn’t make sense to call it a decade). What date did that occur? December 31, year 10. So on January 1, year 11, the second decade began.

Remember:

We are currently in the 21st century and will be until January 1, 2101, when the 22nd century begins.

Again, conversationally I agree that 2 days from now will feel more significant than 368 days from now. But I like to be fair and I think there’s a lot of technical merit from the other argument.

Sigh.

https://xkcd.com/2249/

Cheers!!

And please keep with the contests at .io!

No jazz, just samples and beats.

jazz, samples and beats. it will be great.

Again, a year less to wait untill ITER and the James Webb Telescope…

For the year 2020, I predict…

…I got nothing!

On second thought…

2020 is the year when Brian Benchoff teams up with Warren Buffett and they make a hostile takeover of Rackspace and Hackaday by floating the value of Benchoff Bucks. And that will result in Disney buying up Rackspace and Hackaday for $1.7Bn and making Hackaday Podcasts available on Disney+

Well, still December the 29th here.

Nothing like rushing the clock.

Wouldn’t be funny if everything ends on the 30th … no 2020 at all!

Yep, classic hackaday. Most of the comments are debating semantics and deciding if 2020 is the start of the end of the decade.

Thanks so much for posting articles every day. Let’s hope next decade you guys are posting hacks about 16K VR headsets and cars being fully self driving

hear hear!

Seems cars are already self driving, but under our litigious society, How or Who do you sue first…the lidar sensor or the radar proximity sensor or the doppler that reads the cars speed or…or…or…

Regarding the 2.4GHz harmonics in the RPi4:

The December 2 rpi-update firmware release included a patch to choose an HDMI mode for 2560×1440@60Hz with alternate timing (reduced blanking) to avoid harmonics in the 2.4GHz band.

(No idea how well that works though)

And it seems like any random USB C charger/cable works now on the RPi4?

https://www.raspberrypi.org/forums/viewtopic.php?f=63&t=256646&start=175

It’s amazing how widespread the misconception that the new decade begins in 2020 is. I read it everywhere these days, and even from people that I thought are smart enough to not fall for this trap. The excuse that programmers start counting at zero is… well, Calenders weren’t written in C or C++, were they? :)

Out of personal preference, I consider the years that begin with the same digit as being part of that decade. 00-09 = aughts. 10-19 = teens, 20-29 = twenties, etc. It would seem odd (to me) to consider 21-30 as a decade. Probably derives from my age being zero indexed. I wasn’t a teenager when I was 20. So, zero indexing was natural for me from birth, two decades before I became an engineer, where I also prefer zero indexing.